Illustration by Mark Smith

Please remember that the value of an investment can fall and you may not get back the amount invested.

You’re surrounded. From your washing machine and smartphone to your car and microwave oven, semiconductors are everywhere. About 1.1tn chips are sold to product makers a year – roughly 140 for every person on the planet.

Moreover, semiconductor use is set to keep rising over the very long term. Sectors such as healthcare and education are only just starting to use digital tools in earnest. The internet and smartphones helped drive this, and over the coming years we expect artificial intelligence will accelerate the trend.

Historically, Moore’s Law was the key to unlocking new capabilities, as smaller transistors – tiny switches that turn on and off billions of times a second – made it possible to pack more on a chip. At the peak of the PC revolution, the performance of CPUs (central processing units) – computers’ ‘brains’ – improved 100-fold over 10 years.

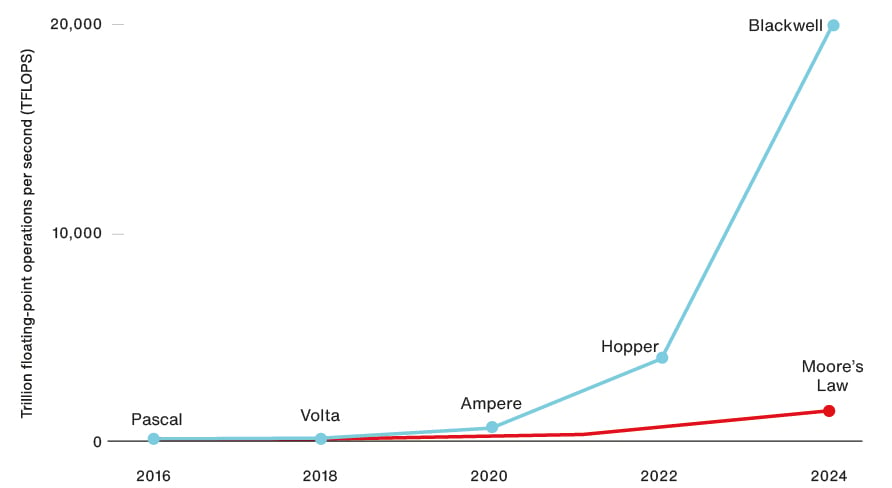

More recently, however, Monks’ holding NVIDIA has made even faster gains with its GPUs (graphics processing units), which are particularly adept at AI tasks.

In March, chief executive Jensen Huang said that the performance of its top-of-the-range chips had increased 1,000-fold in eight years. This lets its customers develop larger, more complex AI models, fuelling breakthroughs in chatbots, image recognition and autonomous driving.

Accelerating performance

NVIDIA’s top AI chip, Blackwell, is 1,000 times more powerful than its equivalent eight years ago

Source: NVIDIA

NVIDIA became one of the few companies to achieve a $3tn valuation earlier this year, thanks to surging demand for its products. But other companies further ‘upstream’ that enable its success have also benefited, as has Monks. We took advantage of a post-Covid slump in semiconductor-related stocks to increase our exposure to the sector in 2022 and 2023.

Shrinking transistors

Chief among these is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s leading producer of advanced chips. Two trends are driving its growth: the complexity and size of the semiconductors it manufactures are both increasing.

One reason chips have become faster and more capable over time is that they contain ever-increasing numbers of transistors. NVIDIA’s new Blackwell GPU features a record-setting 208bn. If you laid the same number of £1 coins side-by-side, they could stretch to the moon more than 12 times over.

To achieve this density and limit energy use, TSMC makes each generation of transistors smaller than the last and layers more of them vertically above each other in a process called 3D stacking. It also charges more for the privilege. In 2014, the firm reportedly sold its densest wafer for $3,000. By 2020, the price was $16,000. Today, the sum is over $20,000.

Simultaneously, high-end chips are getting physically larger, meaning fewer can be fitted on and carved out of each wafer. Blackwell, for example, is twice the size of its predecessor, Hopper. This, again, is driving TSMC’s sales upwards.

Making memory

AI is also fuelling demand for high-performance memory, favouring another of Monks’ holdings, Samsung Electronics.

Building the models that power modern chatbots involves optimising billions of variables. The quicker those parameters and associated training data can be accessed, the faster the process.

This concept, known as memory bandwidth, is often the biggest bottleneck. Samsung is the largest supplier of memory and one of only three companies capable of supplying ‘high-bandwidth memory’ needed for AI training.

Putting those models to practical use, what’s known as ‘inference’, is also memory intensive. Datacentres use Samsung’s memory to run smart assistants and support the increasing number of AI features offered by Microsoft, Alphabet and Meta, among our other holdings. In addition, as we deploy AI into the real world, so-called ‘end devices’, such as smartphones, PCs and cars, also need more memory to run AI services locally.

Monks also invests in ‘enablers’ whose products make manufacturing the chips described above possible. One of these is the Dutch firm ASM International.

In particular, the firm accounts for over 50 per cent of the market in atomic layer deposition (ALD). This involves placing ultra-thin, highly uniform layers of material on silicon wafers, which makes the 3D stacking of transistors possible and minimises electrical current leakage.

One analogy is building a sandwich. Imagine you have a very thin slice of bread and repeatedly add single layers of cheese and ham. ALD uses special gases to add one ‘ingredient’ layer at a time to a surface, which helps make very thin and precise coatings for semiconductors. Some layers conduct electricity, while other layers insulate, giving the silicon wafer its ‘semiconductor’ properties.

Clean rooms and contaminants

Entegris is another firm with a market-leading position in its semiconductor market segment. The US-based company makes the gases and liquids used to purify the clean rooms where chips are made and high-purity chemicals to make the final products erosion-resistant.

Airborne particles invisible to the naked eye can cause chips to malfunction or completely fail, and as transistors continue to shrink, they become susceptible to even smaller contaminants. This increases demand for Entegris’s specialised substances and filters.

Monks also invests in several datacentre ‘enablers’. These include Eaton, the Dublin-headquartered power management specialist. It provides clients with ways to efficiently power racks of computer servers, monitor each rack’s usage and provide backup protection in case of outages.

We also hold Comfort Systems, a specialist in installing and servicing air conditioning and other cooling systems that prevent the servers from overheating. And we own a stake in Stella-Jones, a major supplier of the wooden poles that hold electrical cables overhead across the US and Canada.

These utilitarian examples might seem surprising until you realise that for every £1 spent on datacentre equipment, another 65 pence is spent on the building – things like power management and cooling. Moreover, AI datacentres consume four to five times as much power as traditional equivalents, meaning there needs to be a lot more investment in energy generation and distribution.

Other factors also feed into these three companies’ growth prospects, including the green energy transition, the electrification of transport and the US’s renewed investment in infrastructure.

Cyclical sales

More broadly, we’re mindful of risks. One example is trade tensions between Washington and Beijing. China buys more than 50 per cent of the world’s chips and has a long-term incentive to become less reliant on external suppliers – although some are easier to replace than others.

Another is that, despite AI’s impact, semiconductors are likely to remain cyclical, with periods of oversupply. So if and when valuations become too high, we will adjust our position, just as we did when stocks became undervalued.

That said, part of Monks’ strength lies in the breadth of companies we have invested in, and I’ve only touched on some of the related stocks we hold. The big picture is that the world’s use of semiconductors continues to grow, and there will consequently be multiple winners.

We can’t know for certain where the next waves of disruption will strike or what business models will emerge. However, Monks can pursue long-term growth by investing in a select group of companies that supply the products and tools that underpin the 21st-century economy.

Important information

Investments with exposure to overseas securities can be affected by changing stock market conditions and currency exchange rates.

The views expressed in this article should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. The article contains information and opinion on investments that does not constitute independent investment research, and is therefore not subject to the protections afforded to independent research.

Some of the views expressed are not necessarily those of Baillie Gifford. Investment markets and conditions can change rapidly, therefore the views expressed should not be taken as statements of fact nor should reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Both companies are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and are based at: Calton Square, 1 Greenside Row, Edinburgh EH1 3AN.

The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed on the London Stock Exchange and are not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

A Key Information Document is available by visiting bailliegifford.com

115461 10049578