Key points

It's wrong to credit a handful of western geniuses with revealing the secrets of the universe, according to James Poskett. The science historian introduces Alice Ross to the pioneers left out of our history books.

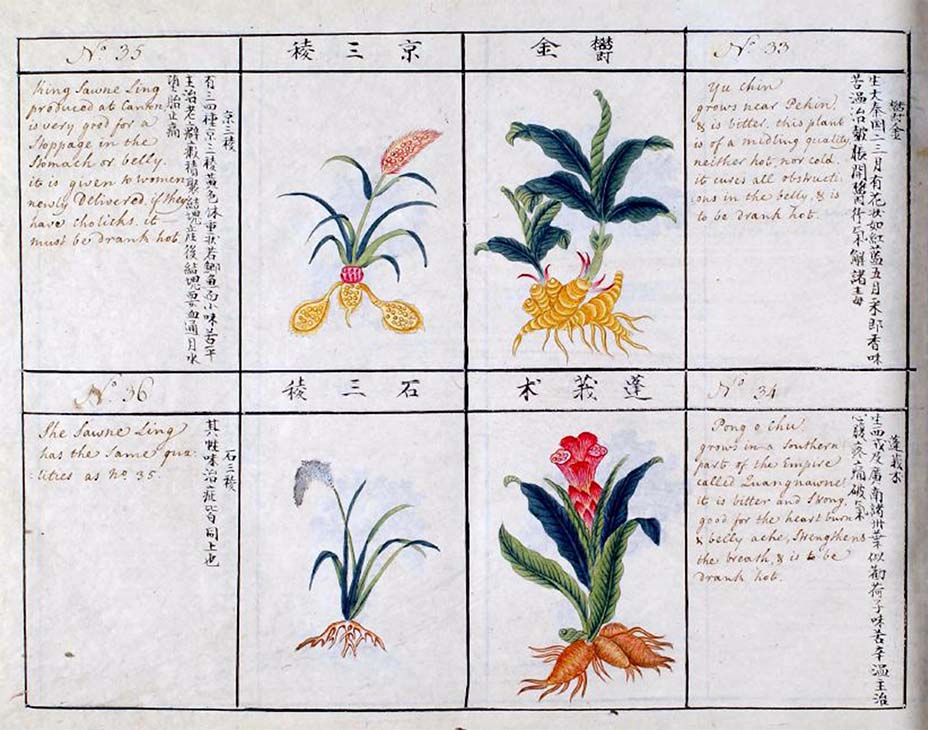

Which visionary scientist first recorded how species adapt and evolve to suit their environment? Kudos if you answered Li Shizhen (1518-1593), Ming Dynasty herbalist and imperial official. Some 300 years before On the Origin of Species, Li had already worked this out. As Darwin himself acknowledged: “The principle of [natural] selection I find distinctly given in an ancient Chinese encyclopaedia”.

In the west we have long been taught to assume that Europeans invented modern science, through lone geniuses such as Copernicus, Newton and Darwin. But this is a myth, argues James Poskett in his book Horizons: A Global History of Science. In fact, “modern science has always depended upon bringing together people and ideas from different cultures around the world”. Li’s little-known influence on Charles Darwin is a case in point.

Poskett, an associate professor in the history of science and technology at the University of Warwick, believes we should view the wider context. “Science is part of history, just like arts and culture and literature and politics,” he says.

The narrative of his book focuses on four key periods of the modern age: The Renaissance scientific revolution, the 18th century age of empire and Enlightenment, the 19th century industrial age, and the post-first world war era, which Poskett sees in terms of conflicting ideologies.

In each section, he explores how a “global cultural exchange”, collaborative and coercive by turns, enabled the thinkers of the day to develop their ideas by standing on the shoulders of those, from ancient Latin America to Africa to Asia, whose discoveries owed little or nothing to western wisdom. His point is that science gained far more from dialogue between disparate traditions than is often acknowledged.

These other scientific traditions, he contends, have been “written out of history”, while Europeans gained the credit. The injustice of Western achievement at the expense of others leaves Poskett seething.

“I am passionate about this, but I'm also grumpy,” the 33-year-old tells me, via Zoom. “This isn't just a happy story about the wonderful globalisation of science. It is also about how the histories of slavery and empire, war, race and ideological conflict have shaped science. Bringing science back down to earth, recognising that the last 500 years of history have been pretty grim, that was what motivated me: realising that there was another story to be told.”

Raised by his single mother in Norfolk, the comprehensive school and Cambridge-educated historian is doing his bit to tell the ‘other story of science’. He submitted a report for a UK parliamentary committee’s inquiry into diversity and inclusion in STEM subjects and is working with London schools to fill in the gaps about non-European science in teaching materials for Black History Month.

How does Poskett think western scientists have been overly heroicised? He cites Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), renowned for his disruptive theory that the earth orbits the sun. Poskett’s book reveals how much the Polish astronomer drew on Arabic and Persian texts. More sinisterly, in a chapter titled “Newton’s slaves”, he reveals how the 17th century Englishman Isaac Newton relied on data collected on slave ships for use in his Principia Mathematica.

One story that particularly ignites Poskett’s ire is that of Satyendra Nath Bose (1894-1974), the Bengali physicist who, along with our contemporary Peter Higgs, gave his name to the Higgs boson particle. Poskett is frustrated that, while Higgs received a Nobel Prize, Bose’s contribution doesn’t even earn a capital letter on the all-important particle’s name. “That's the injustice – that he isn't well-known among non-physicists or non-specialist historians.”

Poskett suspects that Bose’s opposition to the British Raj – the physicist saw research and discovery as a means of national self-realisation – helped alienate him from the Western scientific establishment. “Even though Bose was doing theoretical quantum mechanics, he didn't see science as somehow separate from the world. He saw what he was doing as fundamentally connected with his anti-colonial activism.”

The idea that the history of science has relevance beyond the lecture hall runs through Horizons. By introducing the general reader to scientists who never received the acclaim they deserved, Poskett hopes to change things. “If the book is successful, it will make it easier to go to a TV producer and say, ‘Why don't we do a programme on Indian science?’

“They won't say, ‘What the hell are you talking about?' because these stories are waiting to be told."

14950 10007048

Alice Ross

Alice honed her writing skills at the Daily Mail, before becoming head of press at Royal Collection Trust, promoting HM The Queen’s art collection to the world. She now writes extensively for luxury brands.