Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. This information and other information about the Funds can be found in the prospectus and summary prospectus. For a prospectus and summary prospectus, please visit our website at bailliegifford.com/usmutualfunds. Please carefully read the Fund's prospectus and related documents before investing. Securities are offered through Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC, an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd and a member of FINRA.

China faces many challenges. But extrapolating from its current weakness is a mistake.

To understand the country’s potential, look to nature. After Moso bamboo germinates, there can be little visible growth for years as the plant develops a robust root system. Then, using biological mechanisms that remain a mystery, it can shoot up faster than 1 meter a day to become more than 15 times the height of an adult human and harder than oak.

Likewise, China’s current growth might seem relatively anaemic – gross domestic product (GDP) growth has cooled, home prices are falling, consumer sentiment is weak and its population is shrinking. Coupled with concerns over geopolitical risk and regulatory intervention, it is understandable why international investors are sceptical. But below the surface, China’s government and companies are laying the foundations for the next growth phase.

They include the economy’s transition from property and infrastructure to advanced manufacturing. This involves developing capabilities in areas such as semiconductors, robotics and artificial intelligence and is described as ‘high-quality development’. If done well, it will boost China’s long-term productivity and growth, offsetting the shrinkage of its working-age population.

Battle-tested companies

Investing in China, however, is difficult. Of the roughly 8,000 listed China-based companies, only about 600 have made an average return on capital of more than 10 per cent over the last five years. Put differently, more than 90 per cent of the market hasn’t generated enough returns to justify shareholders’ investment over the period.

Why has long-term performance been so poor? In large part because competition is so intense.

This is a market where change is rapid, capital abundant, consumers fickle and competitive advantage fluid. Furthermore, its scale – a population of over 1.4 billion, an extensive manufacturing base and a rising middle class – also makes it highly attractive to copycats.

While Tesla practically had the electric vehicle (EV) market to itself in the US for years, rivals proliferated in China from almost the start. At one point, Bloomberg reported there were “roughly 500” registered firms involved.

© Imaginechina Limited/Alamy Stock Photo

CATL’s batteries are widely used by Chinese and western electric vehicle makers

That competition eroded returns, but it also weeded out the weakest players. Those that survived, such as Chinese EV manufacturer Li Auto, and their suppliers, including battery maker CATL, are now world-class operators capable of thriving on the global stage.

Overcapacity by design

Some still write off China’s EV industry and other emerging sectors because of overcapacity. As we’ve repeatedly seen in the country, when production exceeds demand, prices fall and profits are squeezed or wiped out. This can cause investors to take fright.

However, for technologies that follow Wright’s Law – the rule-of-thumb that says for each doubling in production, the cost of manufacturing each unit decreases by a constant percentage – overcapacity can create the conditions for long-term competitive advantage. In simple terms, the more you make, the more ways you learn to improve the processes involved, allowing you to increase quality and cut unit costs simultaneously.

It’s how Taiwanese chip manufacturer TSMC leapfrogged its American and Japanese counterparts. And it’s a significant factor in why Chinese firms account for 80 per cent of the world’s solar panel production.

Moreover, adoption curves in new industries tend to be highly predictable, suggesting that the demand for China’s EVs will continue to increase to match the expanding production capacity.

‘Overcapacity’ in newly emerging industries is, therefore, a feature, not a bug. It’s a result of deliberate policies by the Chinese government to build a competitive lead in strategic industries. These policies spur innovation, increase output and reduce prices.

Lower prices benefit consumers and accelerate EV adoption. EV penetration in China will probably exceed 40 per cent this year, compared to a global figure of about 10 per cent.

The move to EVs also has other consequences. It reduces reliance on foreign oil. It cuts pollution and increases air quality. And it creates jobs.

Decoupling’s implications

No conversation about China is complete without touching on geopolitics. However, it would be misguided to group all concerns under the umbrella term ‘China risk’ and suggest you can avoid it by only investing elsewhere.

The US and China’s economies are tightly integrated and mutually dependent. This increases the cost of conflict, discouraging hostile action.

However, in the medium term, rising trade barriers and firms’ acting to localise supply chains could accelerate economic decoupling, reducing the deterrent. This would create risks not only for Chinese companies but also businesses selling into China.

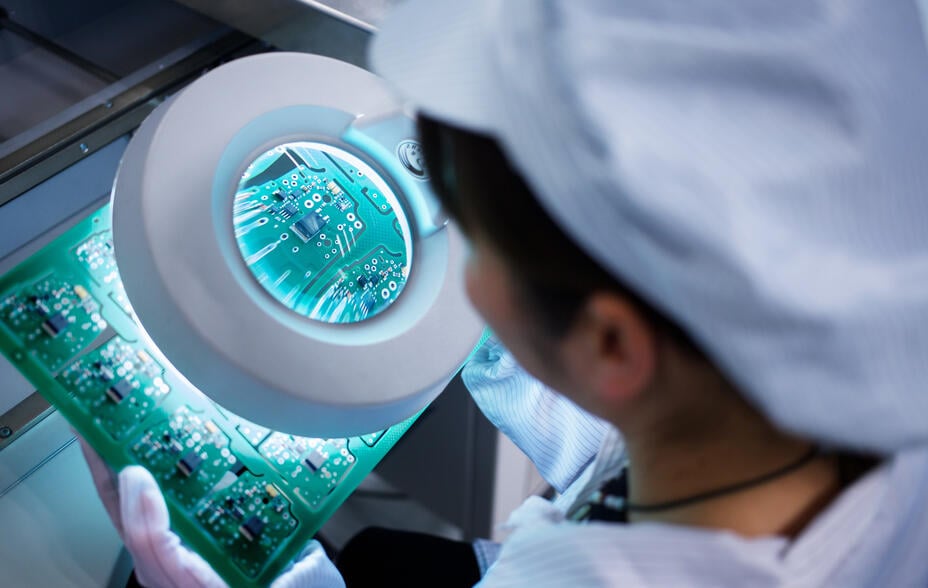

Take, for example, what we’re already seeing with semiconductor localisation. China is the largest chip consumer, purchasing more than half the world’s supply, most of which it imports.

In 2015, its government set targets to reduce that reliance. This became more pressing when Washington introduced semiconductor export restrictions against first telecoms specialist Huawei, then chip manufacturer SMIC, and ultimately across China. Covid added further impetus when many semiconductor makers prioritised orders from large western companies over smaller Chinese ones.

China may never bridge the technology gap in leading-edge logic – processors that act as the ‘brains’ of smartphones, computer servers and artificial intelligence hardware. However, most of the volume is in trailing-edge chips.

Chinese firms are set to commoditise power semiconductors, which control and convert electrical voltage in everything from vehicles to industrial systems and power grids. Next, they could seek to manufacture their own analog chips, which handle real-world signals – including sound, heat, and light – in sensors, medical equipment and other devices. These markets are currently dominated by western firms.

Chinese semiconductor firms are likely to gain ground in trailing-edge chips, including those used to regulate voltage

The takeaway is that western companies are just as exposed to geopolitical risk as Chinese ones. Moreover, as the US and EU consider fresh tariffs on Chinese EVs and energy transition products to protect their domestic industries, this could spiral into a broader trade war.

One obvious target for Chinese retaliation would be western luxury goods. Given that China is the world’s second-biggest market for these products after the US, many companies would find it difficult to avoid the fallout.

Cultivating new growth

The emergence of the Chinese economy has arguably been the greatest economic event since the Industrial Revolution.

Just 25 years ago, the nation accounted for about 3 per cent of the world’s GDP. Today, it’s about 17 per cent, second only to the US. And we expect its rise to continue – not just in terms of economic metrics but also in measures of technological power and advanced manufacturing capability.

For all the complexities that investing in China brings, as a global investor, you cannot ignore it. China will become an increasingly important actor in the global economy. It is tightly woven into international supply chains, being the largest trading partner for eight of the world’s 10 largest economies. Its policies have far-reaching implications for global companies. And its interests and activities span multiple continents.

So, what for portfolios? Returning to my earlier analogy, Moso bamboo has another unusual characteristic. Groves can go more than a century between flowerings. But when they do, each mature stem is prolific in its release of seeds, unleashing fresh growth.

Could China’s investments in advanced manufacturing set the country up for such a rare flowering? What might that mean for the changing world order? If there is one thing I have the highest conviction in it’s that one you cannot hope to understand the world without understanding China.

Important information and risk factors

The Funds are distributed by Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC. Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC is registered as a broker-dealer with the SEC, a member of FINRA and is an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

As with all mutual funds, the value of an investment in the Fund could decline, so you could lose money. International investing involves special risks, which include changes in currency rates, foreign taxation and differences in auditing standards and securities regulations, political uncertainty and greater volatility. These risks are even greater when investing in emerging markets. Security prices in emerging markets can be significantly more volatile than in the more developed nations of the world, reflecting the greater uncertainties of investing in less established markets and economies. Currency risk includes the risk that the foreign currencies in which a Fund’s investments are traded, in which a Fund receives income, or in which a Fund has taken a position, will decline in value relative to the U.S. dollar. Hedging against a decline in the value of currency does not eliminate fluctuations in the prices of portfolio securities or prevent losses if the prices of such securities decline. In addition, hedging a foreign currency can have a negative effect on performance if the U.S. dollar declines in value relative to that currency, or if the currency hedging is otherwise ineffective.

For more information about these and other risks of an investment in the Funds, see “Principal Investment Risks” and “Additional Investment Strategies” in the prospectus. There can be no assurance that the Funds will achieve their investment objectives.

| Company | Baillie Gifford Share Holding in Company (%) |

|---|---|

| CATL | 1.10 |

| Li Auto | 0.32 |

| Tesla | 0.40 |

| TSMC | 1.33 |

Data as of 16 September 2024

116428 10049930