Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. This information and other information about the Funds can be found in the prospectus and summary prospectus. For a prospectus and summary prospectus, please visit our website at bailliegifford.com/usmutualfunds. Please carefully read the Fund's prospectus and related documents before investing. Securities are offered through Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC, an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd and a member of FINRA.

What can we learn from a £20,000 bottle of rare booze?

In 1915, a Chinese drinks maker caused a stir in an international tasting contest at a San Francisco fair. The firm secured an unexpected gold medal after judges favoured its sorghum grain-based spirit.

The decades that followed were tumultuous for this baijiu producer. China endured foreign invasion, civil war and widespread famine before transforming itself into the world’s second-largest economy. And that spirit maker faced disruption of its own, merging with two rivals to become Kweichow Moutai, now one of the nation’s best-known brands.

Against all the odds, some of that 1915 vintage actually survived, stored in a cellar over the decades of upheaval. In 2002, a master blender mixed the venerable liquid with that of more recent years to create an exquisite combination labelled ‘80 years aged’. Today, connoisseurs keep watch for whenever the fine, rare spirit comes up for auction and pay five-figure sums.

The lessons? Foresight and patience.

The world in 2050

Our Emerging Markets Team doesn’t aspire to an 80-year horizon when building portfolios, but we have considered what the world might be like in 2050, with a focus on emerging markets (EM) as a source of growth.

From a global perspective, forecasts suggest:

- GDP could more than double

- The average life expectancy might rise by five years per person, closer to nine years for those in Africa

- The illiterate portion of the population could halve

However:

- The number of people living in cities may rise by 40 per cent to close to 6.7 billion, with overcrowding meaning the faster spread of diseases

- Yields of key crops could fall by close to 10 per cent

- Global waste may increase by around 60 per cent

So, it’s clear that depending on your perspective, the world may be a much better place, or a much worse place over the next quarter century.

But how can we reasonably make any predictions here, anyway? 2050 is too far away. In films, it’s a world of flying cars, humans with chips in their arms, or robots ruling the roost. The point is it seems like an eternity away.

But we’re no further from 2050 than we are from:

- Sony releasing the PlayStation 2 in Japan

- Putin first becoming president of Russia

- India’s population reaching one billion

- Nokia releasing its 3310 handset

The hardy nature of the Nokia 3310, released in 2000, earned it the nickname ‘the brick’. ©H_Ko - stock.adobe.com.

Our industry spends most of its effort on assigning near certainty to events over the next year or two: Fed interest rate movements or China’s latest GDP figures, for example.

This paper addresses bigger shifts in the world. Why would we look as far ahead as a 25-year horizon? Put it in perspective: the average western 30-year-old worker will retire between 33 and 38 years from now and clearly, their savings requirements don’t stop there!

Our goal here is to provide you with food for thought on how the world may change over the longer term, with a particular focus on emerging markets as a source of growth.

A fresh view

Let’s start by trying to visualise what the world might look like in 25 years’ time.

Source: World Mapper, 2025.

The map above is based on the traditional view, the Mercator projection, but it’s been redrawn according to 2050’s population forecasts.

It’s striking just how big Asia and Africa appear. Your mind quickly starts to wonder about the implications. Before we know it, most countries will have more grandparents than grandchildren. Asia’s middle classes will be collectively larger than those of Europe and the US combined. We will find ourselves amid more industrial robots than manufacturing workers.

However, when thinking about this population change, the questions of most interest to us include: what does a different-shaped population mean for global trade? What does it mean for resources? What does it mean for global power shifts?

We are already living in a splintering world. Geopolitics and its many consequences are leading to big divisions. Observers often lazily bucket countries between ‘the west’ and ‘the rest’.

The size difference is already striking. And the harsh truth for North America and Europe is that we are already becoming less significant, not more. ‘The rest’ is growing faster.

As tensions between countries continue to rise, we need to consider how to survive and thrive in a multipolar world.

The ‘three-sphere’ world

Source: Baillie Gifford research, United Nations World Population Prospectus, Council on Foreign Relations, 2024.

Consider the world in three spheres. We can look at the west, the ‘middle earth’ in the centre, where the bulk of people are, and the ‘opposition bloc’ on the right.

The latter includes Russia and China, among other autocratic and authoritarian countries providing each other with mutual support. Like it or not, this 2.3-billion grouping is made up of hugely influential countries. We need to be open-minded to the idea that not doing business with them risks cutting yourself off from cheap resources and first-rate technologies. It also risks higher inflation and a lowering of productivity.

However, what is most interesting in the context of power shifts to us is the middle earth, as we have termed it. Geopolitical narratives often overlook this group of countries. But this sphere includes more than 100 nations with about 5 billion people.

These are countries that don’t want to pick sides. These countries increasingly trade with each other and with both sides of the geopolitical divide. We’re already seeing huge swathes of capital being deployed to retool supply chains in Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia and India. It’s here where we see globalisation alive and well.

The now well-publicised idea of shifting trade is already becoming an economic reality.

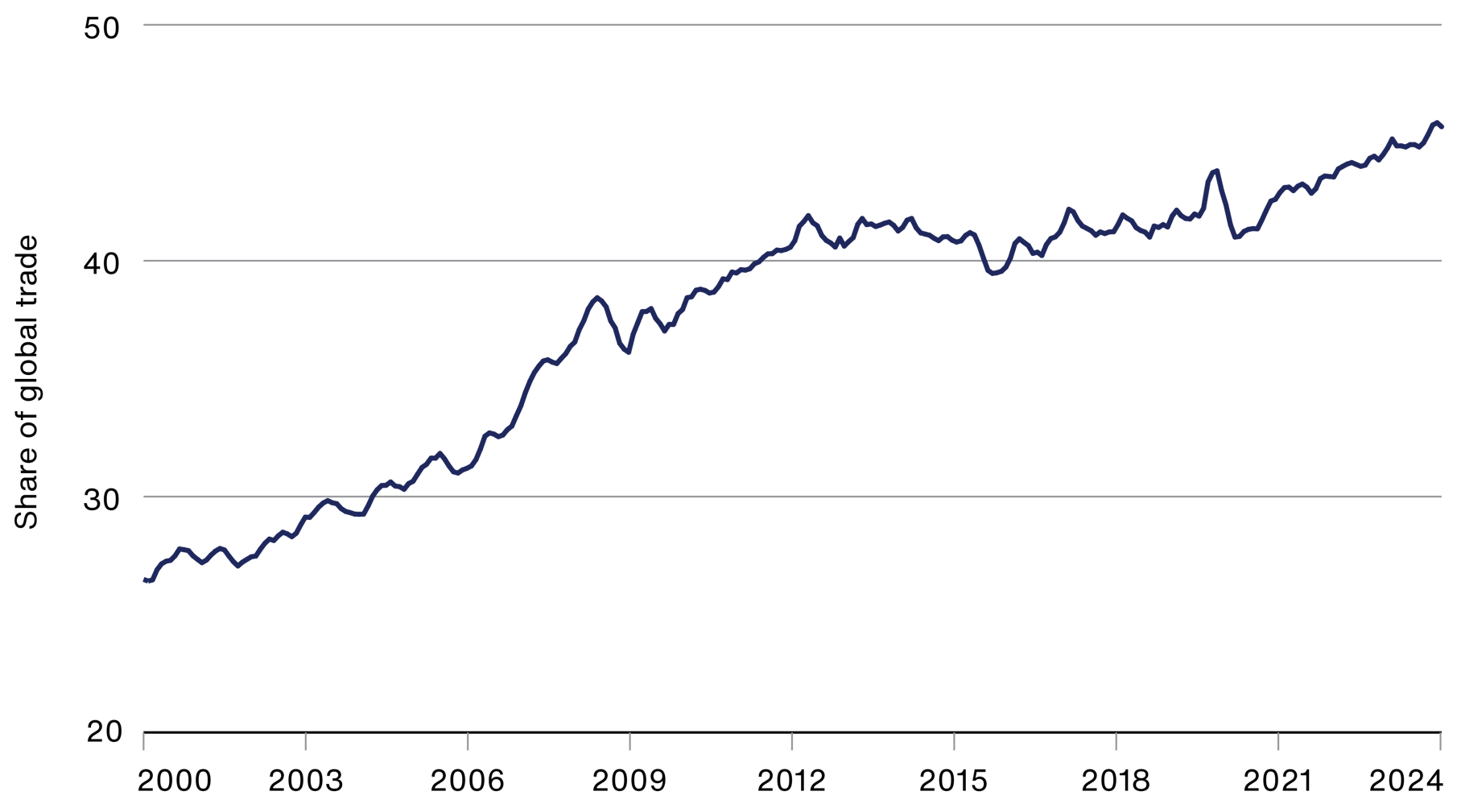

Intra-emerging market trade is growing

Source: IMF, share of EM-to-EM exports in total emerging market exports (3-month moving average). Data to end April 2024.

The chart above illustrates how emerging markets increasingly trade with each other rather than with the west. Intra-emerging-market trade is now at an all-time high; China now exports more to south-east Asia than the US.

The critical takeaway here is the extent to which this trade happens in currencies other than the US dollar. The shift is a gamechanger, and if it continues, it may mean a reduction in US-dollar-based capital and infrastructure spending in many emerging markets countries, as well as the ongoing reduction of dollar use in global foreign exchange reserves.

Lots of trade simply doesn’t need dollars. To give just one example, in 2023, about 20 per cent of global oil trade was settled using other currencies. That’s a stark change from the past.

Under a new model of intra-emerging-market trade, it’s far more likely that counterparties will denominate deals in renminbi, rupees or reals. It’s also far more likely that the profits will be recycled back into emerging markets. And that’s where positive feedback loops kick in.

Investment implications

Where might we want to invest if we extrapolate this trend of a splintering world? Let’s consider three possibilities:

1. Domestic

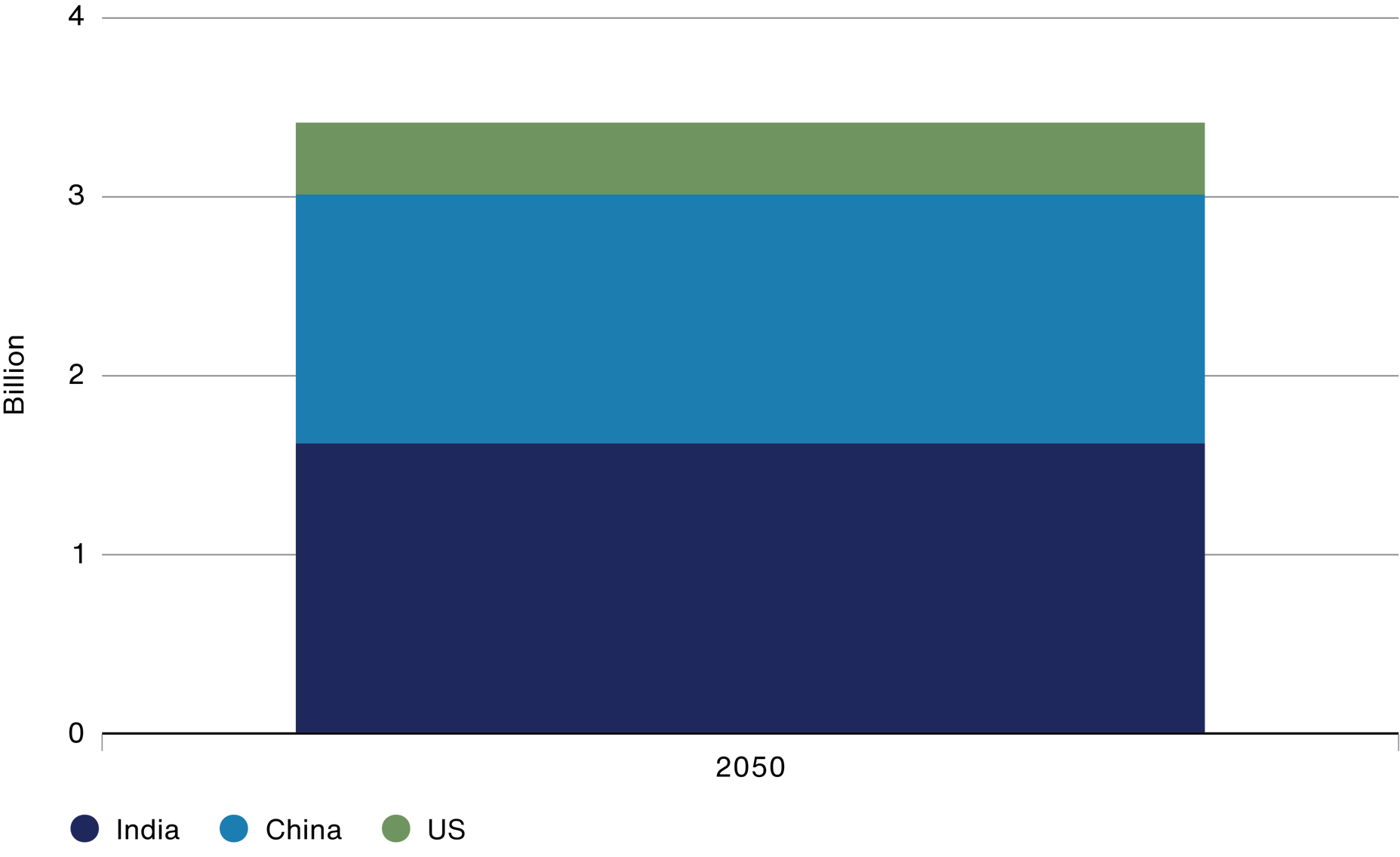

It’s a bit of a cheat, but we could seek to circumvent this trend by looking at countries with domestic markets so large that there are big industries where external trade just isn’t that important. Clearly, we are talking about the likes of China and India here. By 2050, they will be even larger relative to the biggest developed markets. And many of their companies have deep enough pools of local demand such that they need not worry about exports.

Estimated population of US, China and India in 2050

Source: Pew Research Centre, United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, World Population Prospectus. 2012 revision, June 2013.

2. Middle earth

In a splintering world, the aforementioned set of countries that haven’t picked sides is likely to become even more important. Take the likes of Brazil, South Korea, India or Indonesia. They have strong trade relations with both China and the west. After all, both sides will want to consume South Korea’s memory chips, Brazil’s soybeans, India’s IT services or Indonesia’s nickel.

Trading across geopolitical divides

|

|

China as an export partner |

US as an export partner |

|

South Korea |

#1 |

#2 |

|

Brazil |

#1 |

#2 |

|

India |

#3 |

#1 |

|

Indonesia |

#1 |

#2 |

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023.

3. Critical input producers

Given the world’s challenges in the coming decades, the need for critical inputs is only likely to grow. We’ll need critical minerals to build the renewable transition. We’ll need advanced semiconductors to power the AI era. We’ll need steel and cement to retool the new supply chains. Emerging markets are the best and lowest-cost producers of this ‘stuff’.

The recent past demonstrates just how sharply demand for critical inputs can rise: between 2000 and 2022, the total amount of raw materials extracted to meet consumption demand increased by 71 per cent. That was more than twice the rate of global population growth over the same period. Moreover, there is a real chance we need even more infrastructure over the next quarter century.

The critical point is that demand for raw materials tends to grow more sharply than people intuitively expect. And when you consider that EM countries are the biggest producers of copper, nickel and cobalt, among other minerals, it becomes apparent who the west needs to keep onside to achieve its green ambitions.

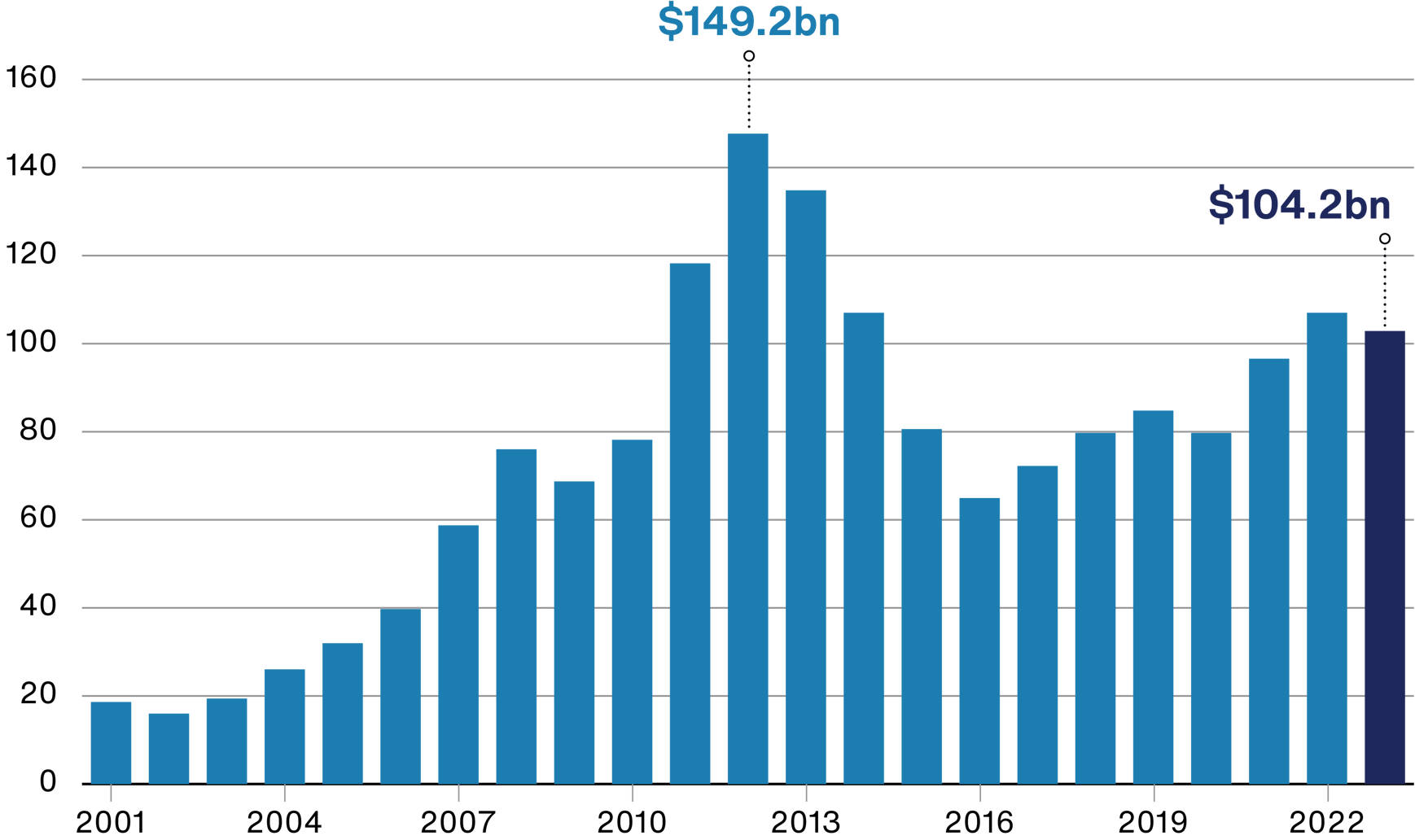

Yet commodity industries appears unprepared. For instance, using the metals and mining industry’s capital expenditure to gauge how much is going into supply, spending is about 30 per cent below its 2012 peak.

Metals and mining industry capital expenditure, US$bn

Source: IEA, BofA Global Research estimates. US dollar. As at May 2024.

This creates all sorts of challenges. However, from an investment point of view, it leads us to consider investing in companies that will benefit from higher prices in these areas.

Oil and gas

It's all fine and well to talk about minerals for the green transition, but in the emerging world, we need to be careful not to overlook ‘traditional energy’. Like it or not, fossil fuels will be relevant for years to come. The demand-and-supply imbalance feels significant here, too.

One way to frame demand is to compare developed and emerging nations’ usage on a per capita basis. By this measure, Canada, for example, consumes about five times as much oil as China.

Oil consumption by country, 2023

Source: Baillie Gifford research, Word Population Review, UN World Population Prospects

As emerging economies grow and their middle-income wealth rises, their energy use increases. But the capital expenditure on oil and gas is more than $300bn shy of 2014’s high.

We expect there to be a positive correlation between energy use and productivity, profitability and job creation in many EM countries over time, which will lead to investment opportunities too.

The internet and the underserved

Beyond ‘commodities’ in the traditional sense, we should also expand the commodity concept to include other basic services that we take for granted in the west. For example, internet that is fast enough to run the applications we need or banking services that allow us to transact and interact without friction.

Populations who do not use the internet

Source: Baillie Gifford, DataReportal, Digital Around the World, 2025.

The graphic above shows that there are still vast numbers of people who aren’t well served for basic needs. Most are in emerging markets.

This online access, or lack thereof, is also among the key reasons for diverging levels of cash dependence. Globally, 16 per cent of point-of-sale spending (including payments made at store tills, restaurant tables and online checkouts) was in cash in 2023, but the figure was significantly higher in many emerging and frontier economies.

Percentage of transactions in cash

Source: Worldpay Global Payments Report, 2024.

This gap will close of course, and the implications of wider data access will be felt well beyond just the traditional EM consumption stories. For instance, mobile technology has already proved to be especially helpful in the healthcare sector.

In Kenya, for example, government agencies use insights derived from mobile data – rather than payroll or school records – to plan healthcare policy and outreach. It’s simply easier to gather, richer in information and more reliable.

Imagine if that were the case in wider Africa or in large parts of Asia. The number of investment opportunities is likely to rise alongside better mobile technology.

Best of both worlds

Here, we return to our original map, but this time overlay examples of areas in which emerging market companies are best positioned to thrive.

Serving the underserved

Sources: Baillie Gifford research/World Bank Open Data/Kepios analysis: DataReportal, Digital Around the World, 2025/Quest Mobile

Could we be on the cusp of the next bull market for this asset class? If the 2000s were about a rising macroeconomic tide lifting all boats in EM (thanks to China’s infrastructure spend), and the 2010s about that tide going out just as a new generation of high-calibre companies came to the fore, is it possible the latter half of the 2020s will be defined by the best of both worlds? In other words, might we see a strong alignment between top-down macroeconomics and the bottom-up universe of exceptional opportunities?

Certainly, emerging markets macro looks strongly resilient, with the International Monetary Fund forecasting economic growth for emerging and developed economies at double the rate of advanced economies. Levels of indebtedness in EM are also relatively low. Coupled with this, we see that the number of world-class companies in EM continues to rise. More than 60 per cent of high-growth stocks in the MSCI ACWI index are emerging markets businesses (where growth is defined as firms forecast to have more than 20 per cent earnings growth in the next three years).

So, if this is the decade in which strong macro meets strong micro for emerging markets, it’s undoubtedly inaccurately represented in today’s investor portfolios.

Global equity fund positioning in emerging markets

-3.1%

average EM weight v ACWI

77%

of funds underweight in EM

Source: FactSet, Copley Fund Research (data for 334 active global funds as of January 2025).

By contrast, sentiment is on its knees. Almost every global fund is underweight in emerging markets stocks. The 3.1 per cent average shortfall quoted above might not seem much, but emerging markets comprise under 10 per cent of the MSCI ACWI.

So, one key 2050 prediction is that this will change. Whether this grouping of countries retains its ‘emerging markets’ designation is another question.

Significantly, according to a JP Morgan report last year, if the weighting reverted to the 20-year average of 8.4 per cent, it would represent inflows of hundreds of billions of dollars.

Investing in the future

Most precise economic projections end up being entirely wrong, so we have steered clear of those in this paper, but that said, we are under no illusions that the nature of looking out a quarter of a century means that it’s highly likely many of the predictions above are off the mark. Despite our best efforts to foresee how the big growth themes will impact returns, we are open-minded to change and willing to adapt our views to fit facts as they unfold as global growth changes.

To us, it would be a surprise if emerging markets don’t continue to gain ground over the long term. We should remember that progress over the last few decades has already been very strong. In 1990, about 57 per cent of the world’s inhabitants lived in low-income countries, as defined by the World Bank. By 2023, that had fallen to just 9 per cent.

Poverty progress

Source: World Bank, 2025.

The world’s global retirement savings gap is currently valued at $70tn, and it’s sobering to think that this is projected to increase to $400tn by 2050.

Should emerging market equities deliver, they’ll be key to shrinking that to a more manageable sum. Surely that merits setting aside some bottles of Kweichow Moutai for a celebratory toast?

Important information and risk factors

The Funds are distributed by Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC. Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC is registered as a broker-dealer with the SEC, a member of FINRA and is an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

As with all mutual funds, the value of an investment in the Fund could decline, so you could lose money. International investing involves special risks, which include changes in currency rates, foreign taxation and differences in auditing standards and securities regulations, political uncertainty and greater volatility. These risks are even greater when investing in emerging markets. Security prices in emerging markets can be significantly more volatile than in the more developed nations of the world, reflecting the greater uncertainties of investing in less established markets and economies. Currency risk includes the risk that the foreign currencies in which a Fund’s investments are traded, in which a Fund receives income, or in which a Fund has taken a position, will decline in value relative to the U.S. dollar. Hedging against a decline in the value of currency does not eliminate fluctuations in the prices of portfolio securities or prevent losses if the prices of such securities decline. In addition, hedging a foreign currency can have a negative effect on performance if the U.S. dollar declines in value relative to that currency, or if the currency hedging is otherwise ineffective.

For more information about these and other risks of an investment in the Funds, see “Principal Investment Risks” and “Additional Investment Strategies” in the prospectus. There can be no assurance that the Funds will achieve their investment objectives.

As at March 31, 2025 Baillie Gifford held Kweichow Moutai. A full list of holdings is available on request and is subject to change.

149908 10054408