Illustration by Anna Higgie

Investors should consider the investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. This information and other information about the Funds can be found in the prospectus and summary prospectus. For a prospectus and summary prospectus, please visit our website at bailliegifford.com/usmutualfunds. Please carefully read the Fund's prospectus and related documents before investing. Securities are offered through Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC, an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd and a member of FINRA.

For Henry Kissinger, it oiled the wheels of diplomacy. “If we drink enough Moutai, we can solve anything,” the US Secretary of State joked to Deng Xiaoping at talks in 1974.

For the emperors of the medieval Tang and Song Dynasties, the baijiu (white spirit) was prized for its quality. Visitors to court were expected to present it as tribute.

I was reminded of all this heritage as we toured the company’s museum at its distillery complex in the town of Moutai in the province of Guizhou (Kweichow in the old Romanisation), a three-hour flight south-west of Shanghai.

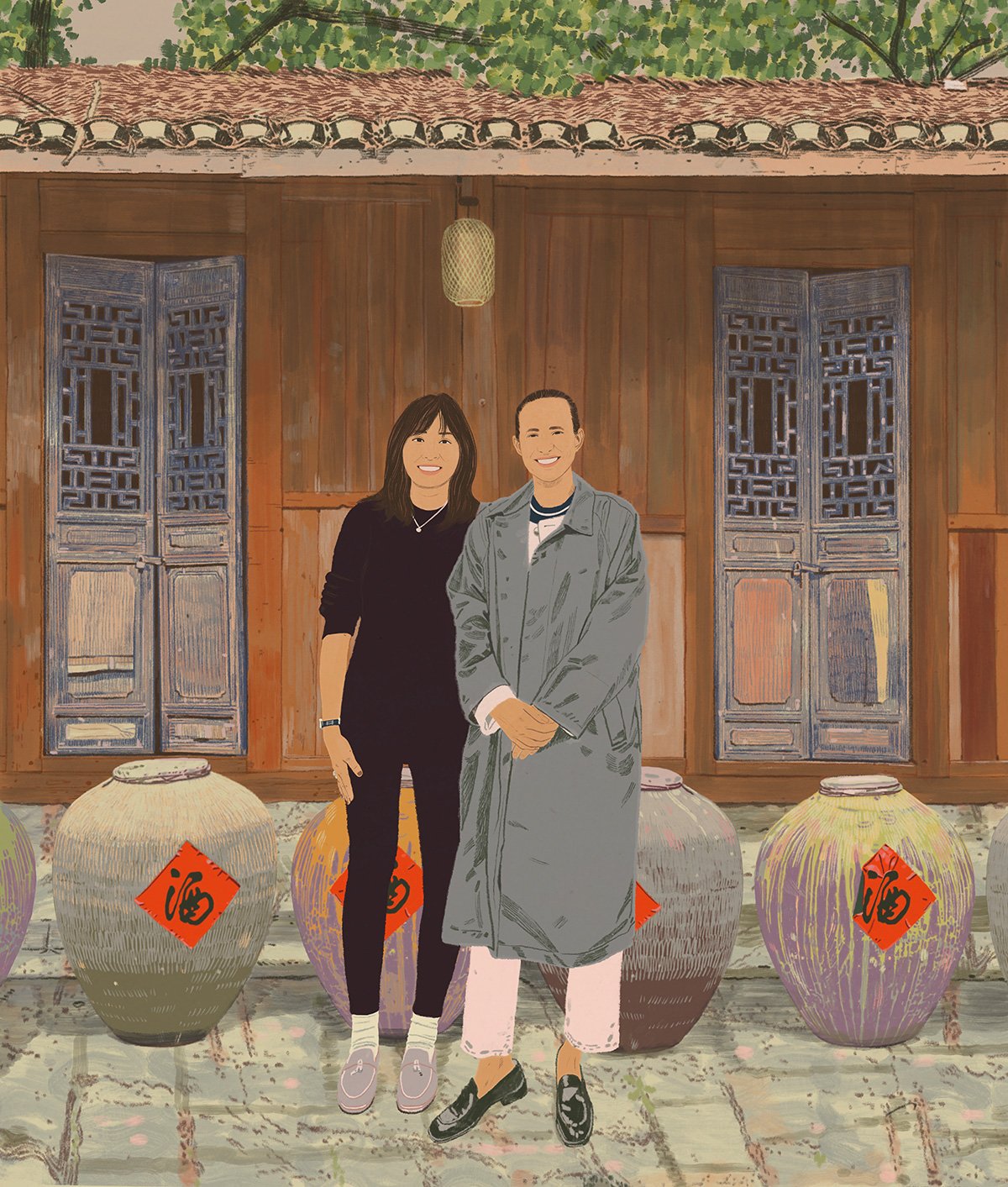

The pervasive sweet scent of fermenting sorghum, an ancient cereal grain, took me back to my first visit seven years ago. This time, my fellow investment manager Sophie Earnshaw was accompanying me. To her, it smelled of “alcoholic soy sauce”.

We were there to catch up with Kweichow Moutai’s chief financial officer and board secretary, Ms Yan Jiang, on the plans and projections of one of China’s largest, most profitable companies. This was Sophie’s first direct encounter with the unique culture of the company that, since overtaking Diageo in 2017, has become the world’s most valuable drinks brand.

With a net profit margin of 79 per cent, Moutai has achieved a kind of modern-day alchemy, turning the base elements of sorghum, water and yeast into liquid gold. We think it has the key ingredients of an exceptional stock: steady revenue growth projected in the mid-teens annually, a rock-solid competitive position and the longevity that comes with symbolising status and celebration wherever Chinese people get together.

Moutai achieved this by mixing ancient methodology with modern science and having a business and governance model that combines partial public ownership, commercial flair and fastidious strategic planning.

Although the drink comes in 16 varieties, much of that profit is earned by its 53-per-cent-proof flagship product, Feitian (flying fairy), whose distinctive red-ribboned white bottles retail for about £200. Feitian makes up around 80 per cent of the company’s £16bn of annual sales.

Family ties

I’ve known this product nearly all my life. Growing up in Chongqing in Sichuan, whose spicy food pairs perfectly with Moutai, my grandfather would call for a bottle whenever celebration was in order.

Today, no family occasion, business deal or diplomatic ceremony is complete without toasts and shots of the fiery liquor with a sweet aftertaste. When my son was born, I bought some bottles of the Year of the Pig special edition to lay down for him to enjoy in adulthood. A friend bought a lot more in anticipation of her newborn daughter’s future wedding party.

Linda Lin (left) and Sophie Earnshaw visited Kweichow Moutai on a fact-finding trip to China in April

Other baijiu are available, but for wealthy or aspirational Chinese it has to be Kweichow Moutai. Anyone offered an alternative would take note that they – or the occasion – were deemed unworthy of the best.

It’s this brand value and the rarity enforced by natural supply constraints that give Kweichow such formidable pricing power. A colleague recently described it as having “the best licence to print money I’ve seen since Microsoft in 1996”.

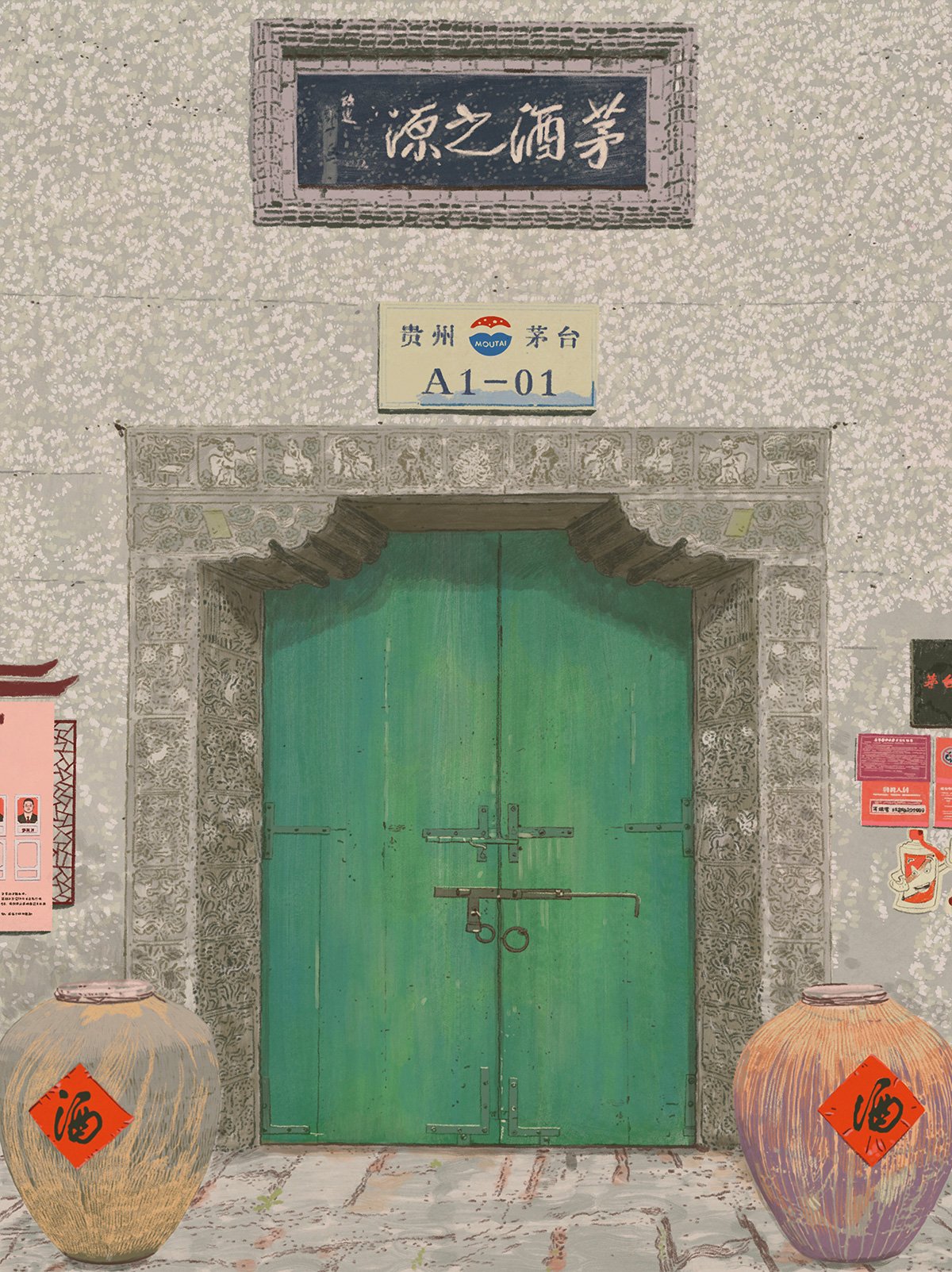

Spending time in the distillery complex is like stepping back into the distant past. One ancient-looking doorway features the inscription mao jiu zhi yuan (the origin of Moutai). This place hasn’t been recreated for tourists but instead reflects the company’s obsession with preserving the drink’s authenticity and artisanal heritage.

Everywhere, there are rows and stacks of dark-grey ceramic jars ready to be filled with yeast or the fermentation base liquor known as qu. They add sorghum to this at the start of a labour-intensive cycle of steaming, fermenting, drying, grinding, distilling and for Feitian – the equivalent of single malt Scotch – ageing.

Still following the ‘24 solar terms’ of the ancient Chinese agricultural calendar, this intricate multi-stage process has been handed down from master to apprentice through the centuries. The fact that it has changed so little is a testament to an obsession with the integrity of the brand and the unwavering pursuit of quality.

Uncompromising on quality

Kweichow Moutai resists the temptation to modernise or accelerate processes for the sake of productivity gains. That said, its master blenders have applied modern data analytics to production records to reduce waste from about 35 per cent to as low as 5 per cent, as well as to monitor ground and weather conditions.

Moutai controls the whole supply chain, growing its own sorghum to ensure quality and security of supply and to protect the local ecosystem. As locals kept telling us, the drink is inseparable from its natural environment: the soil, the water and the air, none of which can be replicated elsewhere. Master distillers who have left the company and tried to apply their experience elsewhere have all failed.

Local pride is unsurprising given that the company employs a third of the town’s population, with some families having worked for it across multiple generations. But increasingly it recruits the brightest and best graduates from Beijing and Shanghai, paying big-city salaries for their expertise in environmental science, data analysis, marketing and other skills key to the firm’s future.

The environmental obsession is notable in a country where enforcement of standards is erratic. Here, Moutai’s ownership model certainly helps. Guizhou’s provincial government has a 35 per cent stake in the business and can enforce strict environmental standards that rival baijiu makers struggle to meet. It can also influence neighbouring 40 Sichuan, from whence flows the all-important Chishui River.

Partial state ownership, grounded in the drink’s links to the foundation mythology of the People’s Republic, has also helped ingrain an ultra-cautious culture whereby every decision is carefully weighed for potential damage to the brand.

Political connections have involved it in past corruption scandals, but its reformed governance now involves more collective endeavour, overseen by multiple stakeholders. They include capable local officials who are acutely aware of the importance of company profitability to their tax take. A mix of expert non-executives from academia and elsewhere, as well as political appointees, provide board oversight.

It all amounts to a system of checks and balances that ensures change is only ever incremental. It wouldn’t work for a fast-moving consumer goods firm or a tech company but suits a successful luxury brand.

Bright future

The big question regarding future growth projections is whether the younger generation wants to drink Moutai and whether they will see it, as I do, as part of their family culture. That’s certainly the company’s intention.

Sophie and I tucked into Moutai ice cream, which the company launched more to increase brand awareness than as a money-spinner. It has also partnered with another Baillie Gifford holding, Luckin Coffee, to launch a hit range of baijiu-flavoured lattes and the like. There are moves to globalise the brand, but this seems to me a ‘nice-to-have’ given the easier routes to grow in the vast and increasingly prosperous Chinese market.

You would expect extended growth horizons from a business whose product has 3,500 years of tradition behind it. As investors, we pride ourselves on the long-termism of our outlook, but meetings with Kweichow Moutai make us think we’ve met our match. While we focus on its growth prospects for the next five to 10 years, it is thinking about the next 100.

Important information and risk factors

The Funds are distributed by Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC. Baillie Gifford Funds Services LLC is registered as a broker-dealer with the SEC, a member of FINRA and is an affiliate of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co unless otherwise stated.

As with all mutual funds, the value of an investment in the Fund could decline, so you could lose money. International investing involves special risks, which include changes in currency rates, foreign taxation and differences in auditing standards and securities regulations, political uncertainty and greater volatility. These risks are even greater when investing in emerging markets. Security prices in emerging markets can be significantly more volatile than in the more developed nations of the world, reflecting the greater uncertainties of investing in less established markets and economies. Currency risk includes the risk that the foreign currencies in which a Fund’s investments are traded, in which a Fund receives income, or in which a Fund has taken a position, will decline in value relative to the U.S. dollar. Hedging against a decline in the value of currency does not eliminate fluctuations in the prices of portfolio securities or prevent losses if the prices of such securities decline. In addition, hedging a foreign currency can have a negative effect on performance if the U.S. dollar declines in value relative to that currency, or if the currency hedging is otherwise ineffective.

For more information about these and other risks of an investment in the Funds, see "Principal Investment Risks" and "Additional Investment Strategies" in the prospectus. There can be no assurance that the Funds will achieve their investment objectives.

| Company | Baillie Gifford Share Holding in Company (%) |

| Kweichow Moutai | 0.45 |

| Luckin Coffee | 3.14 |

As at 16 September 2024. Holdings are subject to change.