As with any investment, your capital is at risk.

What can we learn from a £20,000 bottle of rare booze?

In 1915, a Chinese drinks maker caused a stir in an international tasting contest at a San Francisco fair. The firm secured an unexpected gold medal after judges favoured its sorghum grain-based spirit.

The decades that followed were tumultuous for this baijiu producer. China endured foreign invasion, civil war and widespread famine before transforming itself into the world’s second-largest economy. And that spirit maker faced disruption of its own, merging with two rivals to become Kweichow Moutai, now one of the nation’s best-known brands.

Against all the odds, some of that 1915 vintage actually survived, stored in a cellar over the decades of upheaval. In 2002, a master blender mixed the venerable liquid with that of more recent years to create an exquisite combination labelled ‘80 years aged’. Today, connoisseurs keep watch for whenever the fine, rare spirit comes up for auction and pay five-figure sums.

The lessons? Foresight and patience.

The world in 2050

Our Emerging Markets Team doesn’t aspire to an 80-year horizon when building portfolios, but we have considered what the world might be like in 2050, with a focus on emerging markets (EM) as a source of growth.

From a global perspective, forecasts suggest:

- GDP could more than double

- The average life expectancy might rise by five years per person, closer to nine years for those in Africa

- The illiterate portion of the population could halve

However:

- The number of people living in cities may rise by 40 per cent to close to 6.7 billion, with overcrowding meaning the faster spread of diseases

- Yields of key crops could fall by close to 10 per cent

- Global waste may increase by around 60 per cent

So, it’s clear that depending on your perspective, the world may be a much better place, or a much worse place over the next quarter century.

But how can we reasonably make any predictions here, anyway? 2050 is too far away. In films, it’s a world of flying cars, humans with chips in their arms, or robots ruling the roost. The point is it seems like an eternity away.

But we’re no further from 2050 than we are from:

- Sony releasing the PlayStation 2 in Japan

- Putin first becoming president of Russia

- India’s population reaching one billion

- Nokia releasing its 3310 handset

The hardy nature of the Nokia 3310, released in 2000, earned it the nickname ‘the brick’. ©H_Ko - stock.adobe.com.

Our industry spends most of its effort on assigning near certainty to events over the next year or two: Fed interest rate movements or China’s latest GDP figures, for example.

This paper addresses bigger shifts in the world. Why would we look as far ahead as a 25-year horizon? Put it in perspective: the average western 30-year-old worker will retire between 33 and 38 years from now and clearly, their savings requirements don’t stop there!

Our goal here is to provide you with food for thought on how the world may change over the longer term, with a particular focus on emerging markets as a source of growth.

A fresh view

Let’s start by trying to visualise what the world might look like in 25 years’ time.

Source: World Mapper, 2025.

The map above is based on the traditional view, the Mercator projection, but it’s been redrawn according to 2050’s population forecasts.

It’s striking just how big Asia and Africa appear. Your mind quickly starts to wonder about the implications. Before we know it, most countries will have more grandparents than grandchildren. Asia’s middle classes will be collectively larger than those of Europe and the US combined. We will find ourselves amid more industrial robots than manufacturing workers.

However, when thinking about this population change, the questions of most interest to us include: what does a different-shaped population mean for global trade? What does it mean for resources? What does it mean for global power shifts?

We are already living in a splintering world. Geopolitics and its many consequences are leading to big divisions. Observers often lazily bucket countries between ‘the west’ and ‘the rest’.

The size difference is already striking. And the harsh truth for North America and Europe is that we are already becoming less significant, not more. ‘The rest’ is growing faster.

As tensions between countries continue to rise, we need to consider how to survive and thrive in a multipolar world.

The ‘three-sphere’ world

Source: Baillie Gifford research, United Nations World Population Prospectus, Council on Foreign Relations, 2024.

Consider the world in three spheres. We can look at the west, the ‘middle earth’ in the centre, where the bulk of people are, and the ‘opposition bloc’ on the right.

The latter includes Russia and China, among other autocratic and authoritarian countries providing each other with mutual support. Like it or not, this 2.3-billion grouping is made up of hugely influential countries. We need to be open-minded to the idea that not doing business with them risks cutting yourself off from cheap resources and first-rate technologies. It also risks higher inflation and a lowering of productivity.

However, what is most interesting in the context of power shifts to us is the middle earth, as we have termed it. Geopolitical narratives often overlook this group of countries. But this sphere includes more than 100 nations with about 5 billion people.

These are countries that don’t want to pick sides. These countries increasingly trade with each other and with both sides of the geopolitical divide. We’re already seeing huge swathes of capital being deployed to retool supply chains in Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia and India. It’s here where we see globalisation alive and well.

The now well-publicised idea of shifting trade is already becoming an economic reality.

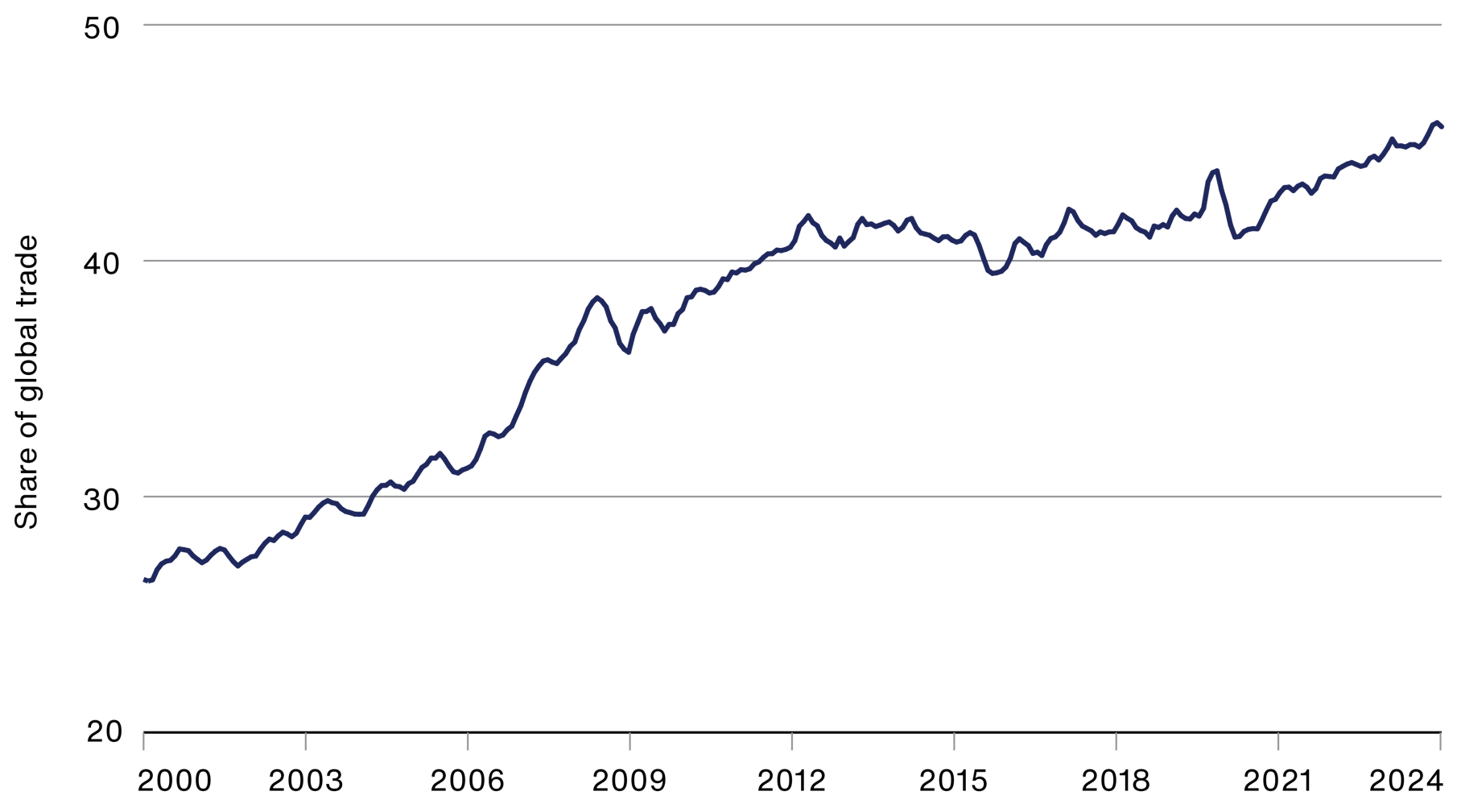

Intra-emerging market trade is growing

Source: IMF, share of EM-to-EM exports in total emerging market exports (3-month moving average). Data to end April 2024.

The chart above illustrates how emerging markets increasingly trade with each other rather than with the west. Intra-emerging-market trade is now at an all-time high; China now exports more to south-east Asia than the US.

The critical takeaway here is the extent to which this trade happens in currencies other than the US dollar. The shift is a gamechanger, and if it continues, it may mean a reduction in US-dollar-based capital and infrastructure spending in many emerging markets countries, as well as the ongoing reduction of dollar use in global foreign exchange reserves.

Lots of trade simply doesn’t need dollars. To give just one example, in 2023, about 20 per cent of global oil trade was settled using other currencies. That’s a stark change from the past.

Under a new model of intra-emerging-market trade, it’s far more likely that counterparties will denominate deals in renminbi, rupees or reals. It’s also far more likely that the profits will be recycled back into emerging markets. And that’s where positive feedback loops kick in.

Investment implications

Where might we want to invest if we extrapolate this trend of a splintering world? Let’s consider three possibilities:

1. Domestic

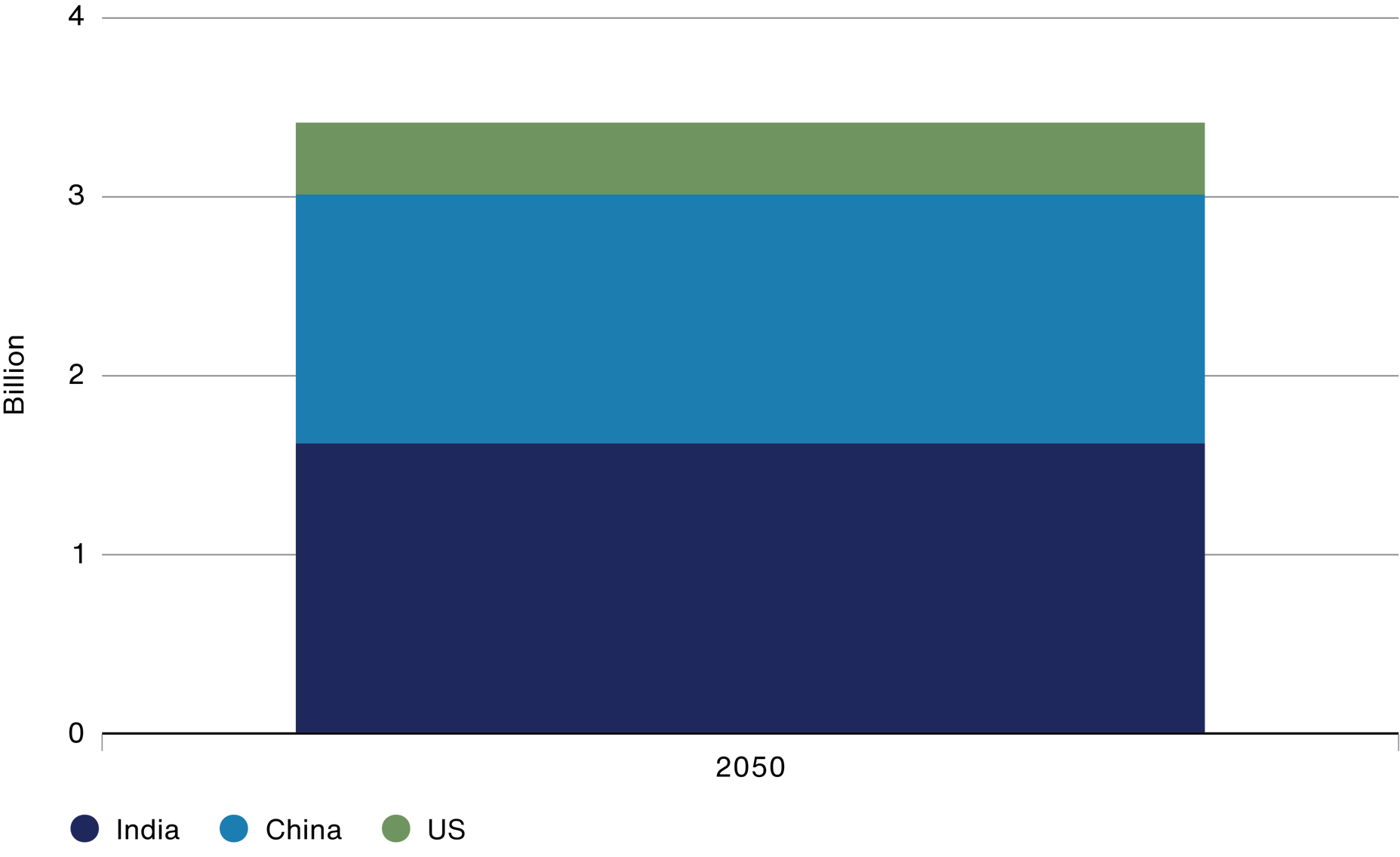

It’s a bit of a cheat, but we could seek to circumvent this trend by looking at countries with domestic markets so large that there are big industries where external trade just isn’t that important. Clearly, we are talking about the likes of China and India here. By 2050, they will be even larger relative to the biggest developed markets. And many of their companies have deep enough pools of local demand such that they need not worry about exports.

Estimated population of US, China and India in 2050

Source: Pew Research Centre, United Nations, Department of Economics and Social Affairs, World Population Prospectus. 2012 revision, June 2013.

2. Middle earth

In a splintering world, the aforementioned set of countries that haven’t picked sides is likely to become even more important. Take the likes of Brazil, South Korea, India or Indonesia. They have strong trade relations with both China and the west. After all, both sides will want to consume South Korea’s memory chips, Brazil’s soybeans, India’s IT services or Indonesia’s nickel.

Trading across geopolitical divides

|

|

China as an export partner |

US as an export partner |

|

South Korea |

#1 |

#2 |

|

Brazil |

#1 |

#2 |

|

India |

#3 |

#1 |

|

Indonesia |

#1 |

#2 |

Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2023.

3. Critical input producers

Given the world’s challenges in the coming decades, the need for critical inputs is only likely to grow. We’ll need critical minerals to build the renewable transition. We’ll need advanced semiconductors to power the AI era. We’ll need steel and cement to retool the new supply chains. Emerging markets are the best and lowest-cost producers of this ‘stuff’.

The recent past demonstrates just how sharply demand for critical inputs can rise: between 2000 and 2022, the total amount of raw materials extracted to meet consumption demand increased by 71 per cent. That was more than twice the rate of global population growth over the same period. Moreover, there is a real chance we need even more infrastructure over the next quarter century.

The critical point is that demand for raw materials tends to grow more sharply than people intuitively expect. And when you consider that EM countries are the biggest producers of copper, nickel and cobalt, among other minerals, it becomes apparent who the west needs to keep onside to achieve its green ambitions.

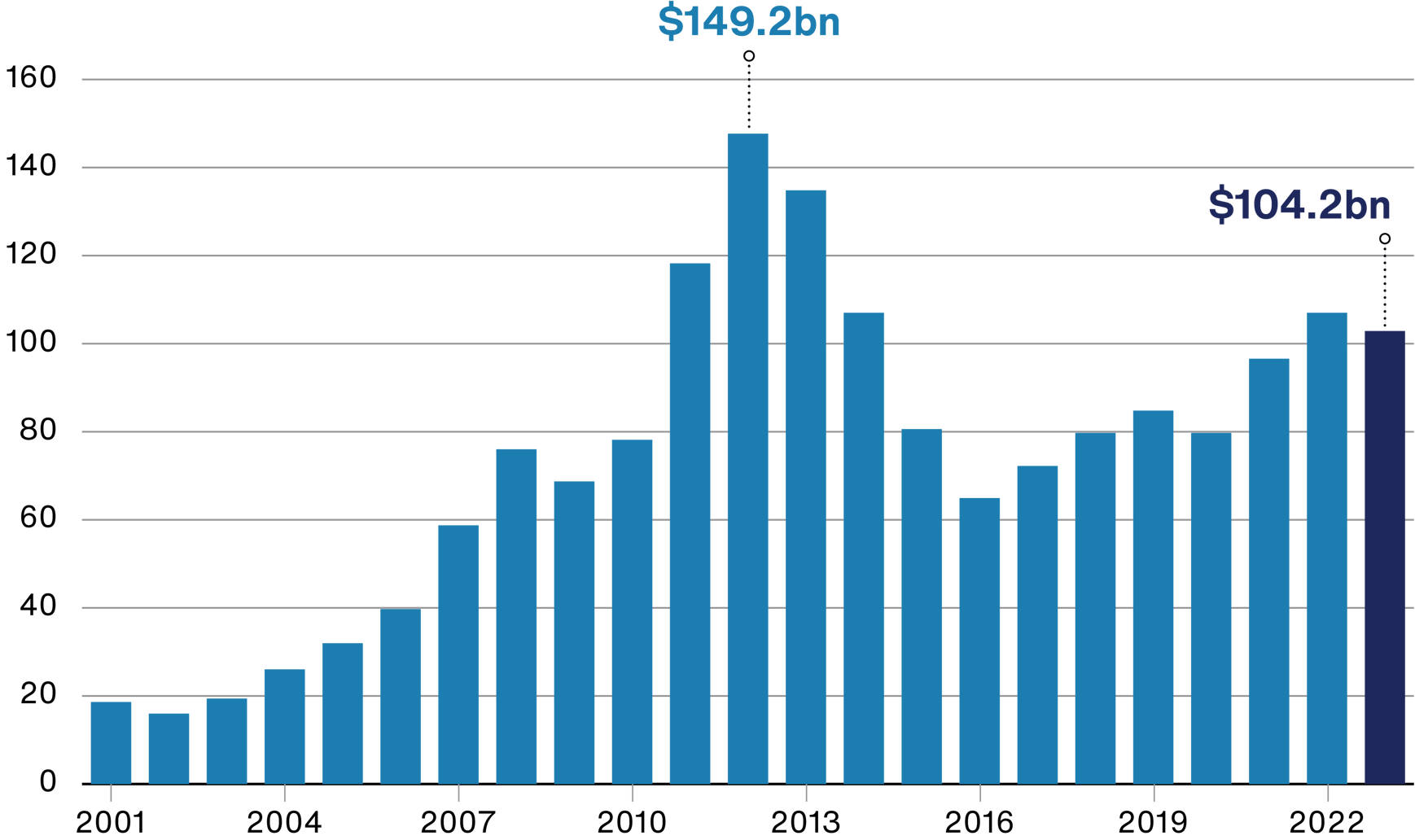

Yet commodity industries appears unprepared. For instance, using the metals and mining industry’s capital expenditure to gauge how much is going into supply, spending is about 30 per cent below its 2012 peak.

Metals and mining industry capex, US$bn

Source: IEA, BofA Global Research estimates. US dollar. As at May 2024.

This creates all sorts of challenges. However, from an investment point of view, it leads us to consider investing in companies that will benefit from higher prices in these areas.

Oil and gas

It’s all fine and well to talk about minerals for the green transition, but in the emerging world, we need to be careful not to overlook ‘traditional energy’. Like it or not, fossil fuels will be relevant for years to come. The demand-and-supply imbalance feels significant here, too.

One way to frame demand is to compare developed and emerging nations’ usage on a per capita basis. By this measure, Canada, for example, consumes about five times as much oil as China.

Oil consumption by country, 2023

Source: Baillie Gifford research, Word Population Review, UN World Population Prospects

As emerging economies grow and their middle-income wealth rises, their energy use increases. But the capital expenditure on oil and gas is more than $300bn shy of 2014’s high.

We expect there to be a positive correlation between energy use and productivity, profitability and job creation in many EM countries over time, which will lead to investment opportunities too.

The internet and the underserved

Beyond ‘commodities’ in the traditional sense, we should also expand the commodity concept to include other basic services that we take for granted in the west. For example, internet that is fast enough to run the applications we need or banking services that allow us to transact and interact without friction.

Populations who do not use the internet

Source: Baillie Gifford, DataReportal, Digital Around the World, 2025.

The graphic above shows that there are still vast numbers of people who aren’t well served for basic needs. Most are in emerging markets.

This online access, or lack thereof, is also among the key reasons for diverging levels of cash dependence. Globally, 16 per cent of point-of-sale spending (including payments made at store tills, restaurant tables and online checkouts) was in cash in 2023, but the figure was significantly higher in many emerging and frontier economies.

Percentage of transactions in cash

Source: Worldpay Global Payments Report, 2024.

This gap will close of course, and the implications of wider data access will be felt well beyond just the traditional EM consumption stories. For instance, mobile technology has already proved to be especially helpful in the healthcare sector.

In Kenya, for example, government agencies use insights derived from mobile data – rather than payroll or school records – to plan healthcare policy and outreach. It’s simply easier to gather, richer in information and more reliable.

Imagine if that were the case in wider Africa or in large parts of Asia. The number of investment opportunities is likely to rise alongside better mobile technology.

Best of both worlds

Here, we return to our original map, but this time overlay examples of areas in which emerging market companies are best positioned to thrive.

Serving the underserved

Sources: Baillie Gifford research/World Bank Open Data/Kepios analysis: DataReportal, Digital Around the World, 2025/Quest Mobile

Could we be on the cusp of the next bull market for this asset class? If the 2000s were about a rising macroeconomic tide lifting all boats in EM (thanks to China’s infrastructure spend), and the 2010s about that tide going out just as a new generation of high-calibre companies came to the fore, is it possible the latter half of the 2020s will be defined by the best of both worlds? In other words, might we see a strong alignment between top-down macroeconomics and the bottom-up universe of exceptional opportunities?

Certainly, emerging markets macro looks strongly resilient, with the International Monetary Fund forecasting economic growth for emerging and developed economies at double the rate of advanced economies. Levels of indebtedness in EM are also relatively low. Coupled with this, we see that the number of world-class companies in EM continues to rise. More than 60 per cent of high-growth stocks in the MSCI ACWI index are emerging markets businesses (where growth is defined as firms forecast to have more than 20 per cent earnings growth in the next three years).

So, if this is the decade in which strong macro meets strong micro for emerging markets, it’s undoubtedly inaccurately represented in today’s investor portfolios.

Global equity fund positioning in emerging markets

-3.1%

average EM weight v ACWI

77%

of funds underweight in EM

Source: FactSet, Copley Fund Research (data for 334 active global funds as of January 2025).

By contrast, sentiment is on its knees. Almost every global fund is underweight in emerging markets stocks. The 3.1 per cent average shortfall quoted above might not seem much, but emerging markets comprise under 10 per cent of the MSCI ACWI.

So, one key 2050 prediction is that this will change. Whether this grouping of countries retains its ‘emerging markets’ designation is another question.

Significantly, according to a JP Morgan report last year, if the weighting reverted to the 20-year average of 8.4 per cent, it would represent inflows of hundreds of billions of dollars.

Investing in the future

Most precise economic projections end up being entirely wrong, so we have steered clear of those in this paper, but that said, we are under no illusions that the nature of looking out a quarter of a century means that it’s highly likely many of the predictions above are off the mark. Despite our best efforts to foresee how the big growth themes will impact returns, we are open-minded to change and willing to adapt our views to fit facts as they unfold as global growth changes.

To us, it would be a surprise if emerging markets don’t continue to gain ground over the long term. We should remember that progress over the last few decades has already been very strong. In 1990, about 57 per cent of the world’s inhabitants lived in low-income countries, as defined by the World Bank. By 2023, that had fallen to just 9 per cent.

Poverty progress

Source: World Bank, 2025.

The world’s global retirement savings gap is currently valued at $70tn, and it’s sobering to think that this is projected to increase to $400tn by 2050.

Should emerging market equities deliver, they’ll be key to shrinking that to a more manageable sum. Surely that merits setting aside some bottles of Kweichow Moutai for a celebratory toast?

Risk factors

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in March 2025 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Important information

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Ltd (BGE) is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. BGE also has regulatory permissions to perform Individual Portfolio Management activities. BGE provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) segregated clients. BGE has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. BGE is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited 柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713–2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a “wholesale client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a “retail client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act.

This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission (‘OSC’). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford International LLC is regulated by the OSC as an exempt market and its licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (‘BGE’) relies on the International Investment Fund Manager Exemption in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755–1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.

Singapore

Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a holder of a capital markets services licence to conduct fund management activities for institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, as a foreign related corporation of Baillie Gifford Asia(Singapore) Private Limited, has entered into a cross-border business arrangement with Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited, and shall be relying upon the exemption under regulation 4 of the Securities and Futures (Exemption for Cross-Border Arrangements) (Foreign Related Corporations) Regulations 2021 which enables both Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford Asia (Singapore) Private Limited to market the full range of segregated mandate services to institutional investors and accredited investors in Singapore.

142804 10053698