High on a shelf in Roman Krznaric's Oxford kitchen, an exotic succulent trails down from a pot, like a living rope of beads. It's called sedum morganianum or, more prosaically, donkey tail and it is 25 years old. Vintage pot plants may not be for everyone, but they are perfect for this house. Because Krznaric is a champion of the long term.

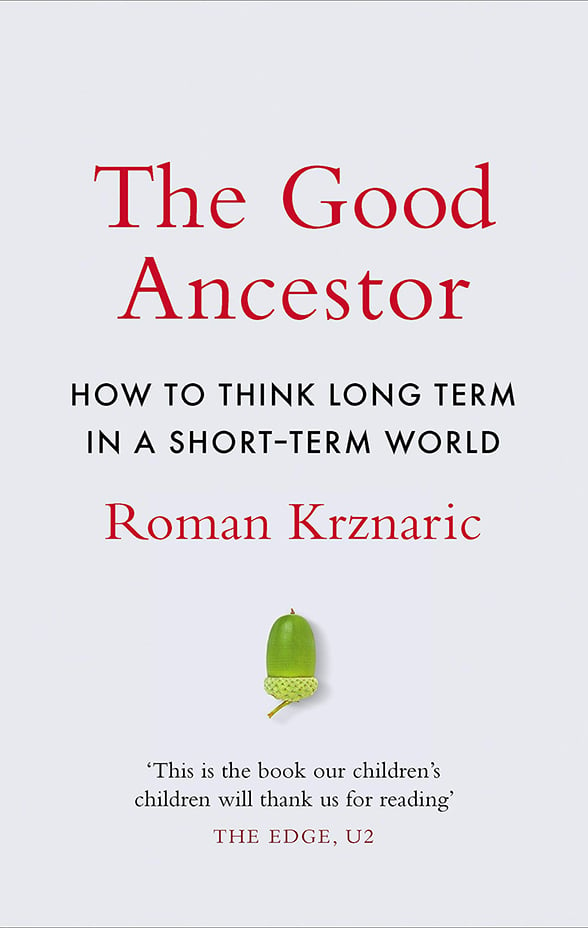

He explains why in his latest book, The Good Ancestor: How to think long term in a short-term world. The phrase was first used by Jonas Salk discoverer of the polio vaccine, who summed up his philosophy in the question: "Are we being good ancestors?". Salk (1914–1995), believed that, just as we have been blessed to inherit riches from the past, we need to hand them on to our descendants.

"My daughter will probably be alive in 2100," Krznaric says. "Her future is not science fiction. Our kids and their kids need to live in a world that will sustain them." That means not using resources faster than they are created, and not leaving waste. "If we are going to think long term, we have to live within the boundaries of the natural planet."

Krznaric was born in Sydney, attending high school in Hong Kong before studying at the universities of Oxford, London and Essex. He taught political science at Cambridge, but then ditched academia to pursue his ideas more actively. He’s a research fellow at the Long Now Foundation, the Californian non-profit organisation that combats short-termism with projects inviting us to imagine life 10,000 years in the future.

Krznaric is not the first to bemoan the blight of short-termism in public, political, business and private life. Lots of people say we need more long-term thinking. But he is exceptionally articulate in explaining what that is and how we can do it.

He suggests six tools to cultivate long-term thinking. One he calls ‘deep-time humility’, where "we grasp the insignificance of our own transitory existence in relation to the vast timeframe of cosmic history". Another is a legacy mindset, which means asking ourselves how we can be remembered well. This goes beyond memorials or bequests for our children, to embrace a practice of everyday life that benefits all future people.

A third tool is intergenerational justice, ensuring a fair and equitable balance between the interests of present and future generations. "Empower the silent majority," Krznaric urges, referring to the trillions yet to be born.

"Treat future generations how you would want past generations to have treated you."

We should also strive after 'cathedral thinking', the kind of long-term vision behind projects such as the British Library, which took 17 years to build and is designed to last 250 years. 'Holistic forecasting', looking decades and centuries into the future, should sketch out broad pathways for our civilisation, while remembering that nothing grows forever.

Finally, have transcendent goals – what astronomer Carl Sagan called "a long-term goal and a sacred project" for all society. In his book, Krznaric advocates ‘one-planet thriving’, meeting the needs of all current and future people while living within the means of a flourishing planet.

Investment has its role in Krznaric’s long-term vision. He is impressed by companies that not only have mission statements with environmental and social goals, but whose ownership and finance is structured to achieve them. Dutch bank Triodos is one. "Triodos can stick to its sustainable principles partly because its shares are held in a trust and traded on their own platform, rather than traded on public markets where they are subject to short-term financial pressures," he says.

He thinks short-termism in stock markets could be limited by a supplementary tax on trades, as proposed by former Silicon Valley chief executive officer Jeremy Lent. Lent suggests a 10 per cent tax if held for less than a day, with the percentage scale gradually descending to 1 per cent if up to 20 years, and 0 per cent thereafter.

Most of all he believes in putting money into things that solve problems in the world, like education and healthcare, or 'circular' companies with recycling at their centre.

"Is investing in keeping with safe planetary boundaries?" Krznaric asks. "If not, don't do it, because you'll be creating the kind of world that our children can't live in. I'm not saying you shouldn't make money, but you need to have triple bottom line accounting – financial, social and environmental."

Far-sighted few

Roman Krznaric's choice of thinkers and protagonists showing the way to be good ancestors.

- Jonas Salk was an American virologist who created the world's first polio vaccine. He did not patent his discovery. When asked why, he answered, "Could you patent the sun?" It was Salk who first coined the phrase "the good ancestor".

- Kim Stanley Robinson is an American science fiction writer. He has published more than 20 books, many with ecological and political themes, featuring the scientist as hero. In his latest, The Ministry for the Future, humans deal with climate change.

- Sophie Howe is the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, one of the few such roles in the world. She scrutinises public policy to assess its effect on people in years to come. Her interventions have changed policy on land planning, transport and housing.

- Layla F Saad is the author of the best-selling Me and White Supremacy and speaks a lot about being a good ancestor. Indeed, her book's subtitle is How to Recognise Your Privilege, Combat Racism and Change the World.

- Martin Rees is a British cosmologist, astrophysicist and the present Astronomer Royal. In spite of his job, he thinks that before dashing off to Mars we need to learn to live within the biophysical means of the only planet we know that sustains life.

- Fridays for Future is a Greta Thunberg-inspired movement of school students around the world who miss classes, mainly on Fridays, to demand action on climate change.

The Good Ancestor: How to think long term in a short-term world published by WH Allen, a division of Penguin Random House (hardback £20).

Ref: 13809 10004605