© The Print Collector/Getty images

Please remember that the value of an investment can fall and you may not get back the amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Just as the Roaring Twenties were coming to their calamitous end, the Monks Investment Trust (Monks) was launched in London on 6 February 1929. Within months, the Wall Street Crash had banished the boom years across the globe.

Monks was the third in a series of investment trusts launched in the late 1920s by the merchant bank of J.C. im Thurn & Sons from its offices in Austin Friars, an ancient pocket of the City of London that was once headquarters of Henry VIII’s enforcer Thomas Cromwell. The area gets its name from a mediaeval friary, hence the Monks name and those of two predecessors, Friars and Abbots. Their market nickname was ‘the ecclesiasticals’.

Monks was the last trust launched by im Thurn before the crash brought the bank down, along with many others. In its stead, the boards of Monks, Abbots and Friars appointed Baillie Gifford as managers with effect from 30 June 1931.

Monks’ capital structure at this point comprised £600,000 of ordinary shares plus £87,700 of 5 per cent debenture stock. Asset values, according to the typically brief company accounts of that era, had fallen to 29 per cent below their book values. It was hardly the healthiest position for the new managers to take on, with the Depression still raging.

Though annual dividends continued to be paid at a reduced rate of 3 per cent, capital values continued to dip before slowly recovering as the 1930s progressed. By the onset of the second world war, however, matters had improved and asset values had risen.

© Popperfoto/Getty Images

Monks’ annual general meetings were held at Baillie Gifford’s London offices opposite the Royal Exchange at 33 Cornhill throughout the war, notwithstanding the blitz which decimated the area, including Bank Station barely 150 yards away.

The day-to-day running of the portfolio continued, despite all dollar securities having to be exchanged for government securities for the sake of the war effort. By 1945, ordinary stocks, almost 90 per cent of which were invested in UK companies, made up 58 per cent of the portfolio with the balance of 42 per cent in various fixed interest securities.

By July 1946, Monks’ Chairman Lord Geddes was able to tell shareholders: “The value of our investments has risen substantially … there being an appreciation of 44.6 per cent this year, compared with 31.3 per cent a year ago.”

Monks, still less than 20 years old, had survived depression and war, two of the greatest tests in recent financial history. With substantial gearing in the form of a series of debentures, the trust was well placed to benefit from the post-war recovery.

By 1960, the investment portfolio was valued at £5.4 million and rose to £8.3 million by 1964.

© Popperfoto/Getty images

With the 1965 Finance Act, introduced by James Callaghan, chancellor in Harold Wilson’s incoming Labour government, everything changed for investment trusts. Complex new tax regulations were introduced in which, for example, every single fund management transaction created a capital gains tax ‘event’ that had to be documented and accounted for. Though many of these changes were unwound by later legislation, the immediate effect was to burden trusts with onerous extra administration.

The time had come, Baillie Gifford and many others decided, to amalgamate smaller trusts, to cut down paperwork and achieve economies of scale. In the case of Friars, Abbots and Monks, this proved a complex process, despite the similarities between the three portfolios.

The merger in May 1968, left the ‘new’ Monks Investment Trust, temporarily at least, with twelve directors, 454 portfolio holdings and thirteen separate lines of debenture stock, the latter with redemption dates ranging from 1971 to 1990. Total net assets following the amalgamation had risen to £47 million by May 1969, compared with £13 million for the unmerged vehicle a year earlier.

The 1970s would be hallmarked by global economic and market volatility spanning the Middle East, surging UK inflation and the three day week, not to mention industrial unrest and the winter of discontent. Better news came in the form of the development of North Sea oil, leading to the appearance of companies such as Schlumberger, Shell and BP in the trust’s top ten holdings. By the early 1980s, oil and gas and related services comprised over a quarter of Monks’ investments.

© Popperfoto/Getty Images

With the roaring 1980s bull markets, the removal of currency controls and the emergence of Japan as the world’s fastest growing stock market, exciting times lay ahead.

Monks reached its half century in 1979, at which point the now £68 million trust, once focused upon UK securities, had an investment objective “to increase both net asset value and dividend in real terms through international portfolio investment … [irrespective of] the composition of stock market indices.” Aided by this global positioning, by the end of the 1980s, despite the cold shower of the 1987 crash, Monks had emerged as a £292 million vehicle, the net asset value per share of which had increased from 74p to 324p in a decade.

The 1990s began badly for markets with the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the 1991-92 recession and the UK’s foray in and out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Soon, however, markets were marching forwards at pace, fuelled by the internet and technology boom. Monks grew strongly towards the turn of the new millennium. Total net assets breached the £500 million barrier in 1995, reaching a peak of £926 million as the year 2000 dawned, only for the technology bubble to burst, taking all sectors and markets with it. This included portfolios such as Monks that weren’t even invested in the dotcom mushrooms, its managers preferring more staid blue chip companies.

Bear markets never last forever, though in this case it was almost three years before real, positive asset growth was being recorded. Monks advanced once more, with total assets exceeding £1 billion for the first time in early 2006 – the year of the retirement of manager Richard Burns, Baillie Gifford’s joint senior partner, who was replaced by Gerald Smith.

Smith in turn was succeeded by Charles Plowden in April 2015, supported by Spencer Adair and Malcolm MacColl, the team behind Baillie Gifford’s Global Alpha Growth Fund. At this stage, notwithstanding the global banking crisis of 2007-2008, the trust had reached a new peak total asset figure of £1.14bn.

Moody's © Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty Images.

TSMC © Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

Naspers © Bloomberg/Getty Images.

CRH © CRH.

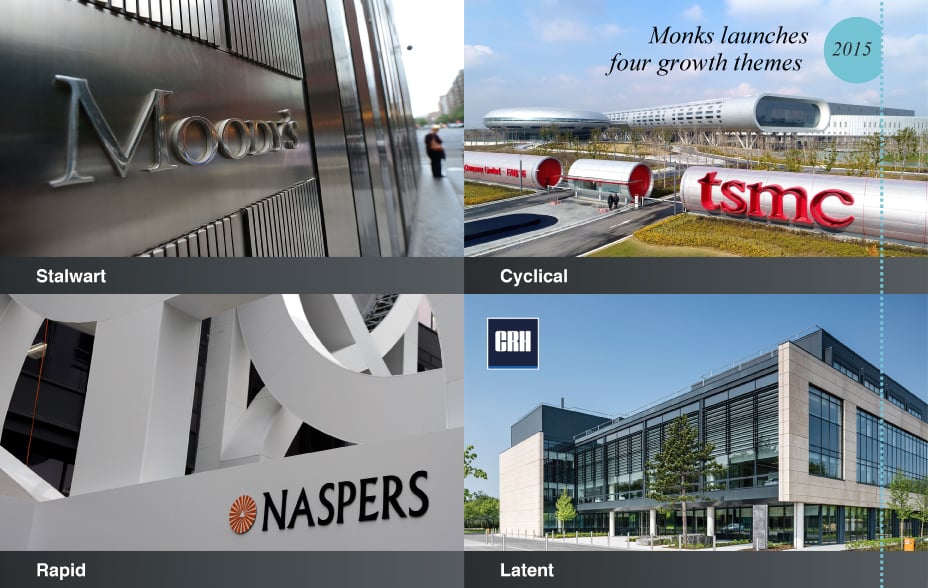

The change of manager was accompanied by a strategic review and a revised investment objective, by creating a portfolio of ‘index agnostic’ global quoted equities, with above average potential for growth, organised around four categories of stocks: ‘growth stalwarts’; ‘rapid growth’; ‘cyclical growth’ and ‘latent growth’. “Harnessing the powers of growth and long-term compounding” took priority over income and dividends. As in 1968, the board prioritised economies of scale. Fees were cut and a structure put in place so that shareholders benefit from lower costs as the trust grew.

By the time of Plowden’s retirement in April 2021, Monks was a £3.3bn investment trust, its scale helping to bring down its expense ratio from 0.58 per cent in 2015 to 0.48 per cent in 2021. It is now managed by Spencer Adair and Malcolm McColl who have tasked themselves with challenging conventional thinking to stay ahead of change in technology, data, cultural shifts, consumer behaviour and many other dynamic forces.

Now in its tenth decade, Monks has come a long way from its birth and infancy in the roaring twenties and hungry thirties, achieving a near-century of growth by anticipating and understanding how global shifts and behavioural changes can lead to profitable investment. Now disruptive new technologies are forcing the pace of change. The trust will need to draw on all of that hard-earned fleetness-of-foot as its second century beckons.

Find out more about Baillie Gifford Monks Investment Trust

Important Information

The views expressed should not be taken as fact and no reliance should be placed upon these when making investment decisions. They should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. If you are unsure whether an investment is right for you, please contact an authorised intermediary for advice.

This article was produced and approved in April 2023 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of recording and may not reflect current thinking.

The trust’s can make use of derivatives which may impact on its performance.

The trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

The trust’s risk could be increased by its investment in unlisted investments. These assets may be more difficult to buy or sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

The trust invests in emerging markets where difficulties in dealing, settlement and custody could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment.

The trust can borrow money to make further investments (sometimes known as “gearing” or “leverage”). The risk is that when this money is repaid by the trust, the value of the investments may not be enough to cover the borrowing and interest costs, and the trust will make a loss. If the Trust's investments fall in value, any invested borrowings will increase the amount of this loss.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed UK companies. The Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

For a Key Information Document for the Monks Investment Trust, please visit our website at www.bailliegifford.com

10018894 36642

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

|

Share Price |

10.0 |

-2.9 |

66.9 |

-17.5 |

-12.7 |

|

NAV |

10.1 |

-4.2 |

67.4 |

-9.4 |

-7.0 |

|

FTSE World Index |

11.1 |

-6.0 |

39.9 |

14.9 |

-0.7 |

Performance source: Morningstar, FTSE, total return in sterling.

Legal Notices

Source: London Stock Exchange Group plc and its group undertakings (collectively, the "LSE Group"). © LSE Group 2021. FTSE Russell is a trading name of certain of the LSE Group companies. "FTSE®" "Russell®", is/are a trade mark(s) of the relevant LSE Group companies and is/are used by any other LSE Group company under license. All rights in the FTSE Russell indexes or data vest in the relevant LSE Group company which owns the index or the data. Neither LSE Group nor its licensors accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the indexes or data and no party may rely on any indexes or data contained in this communication. No further distribution of data from the LSE Group is permitted without the relevant LSE Group company's express written consent. The LSE Group does not promote, sponsor or endorse the content of this communication.