Please remember that the value of an investment can fall and you may not get back the amount invested.

China was still ruled by the Qing Dynasty when Benjamin Newgass formed the General Investors and Trustees Limited (GIT), forerunner of the Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust. The year was 1907, the place, 76 Lombard Street in the heart of the Square Mile.

It was an unimaginably different era in the City as well: the new trust would raise eyebrows sky-high in today’s tightly-regulated financial world. The founding portfolio was created by the purchase of investments from Newgass himself and from his business partner, Harry Kahn, both of whom became directors. Presumably they set their own prices, despite being conflicted as both buyer and seller. The initial capital structure comprised £300,000 in preference stock and the same amount in ordinary stock, standard for the era. What concerned commentators was not the structure but the all-encompassing role of the promoter, seen as a loose cannon in financial circles. As one stock-tipping weekly newspaper fulminated:

“Mr Benjamin Newgass is to act as managing director of the new company, and he is to supply office accommodation and secretarial work in exchange for £1,700 per annum, so that he is vendor, promoter, managing director and secretary.

... we only remark that anyone who subscribes to the shares should, after so doing, consult some medical practitioner who makes a speciality of lunacy cases.”

The Rialto, 1907

Such fears notwithstanding, a closer look reveals that the distribution of assets was conventionally ‘defensive’ in today’s terms. Ordinary shares comprised a mere 18 per cent of the total, outweighed by 62 per cent in mortgages, debentures and bonds. A hefty 37 per cent was invested in the US, 33 per cent in the UK and 20 per cent in Europe, plus tail holdings in other areas.

The trust went on to defy the doom-mongers, not only by staying above water but by continuing to pay dividends right through the First World War, the Great Depression years and beyond.

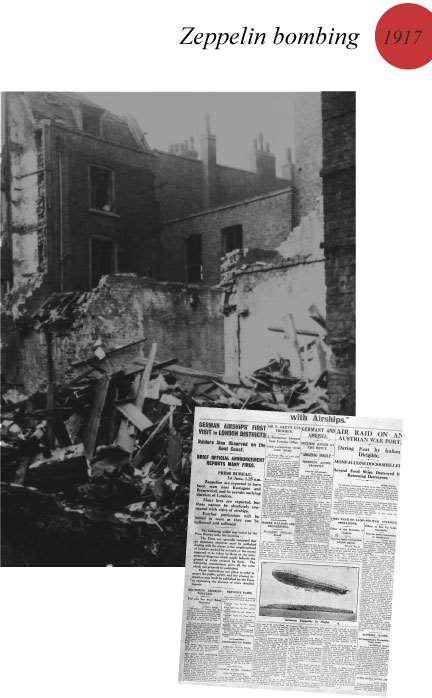

Annual reports give glimpses of the world-shaking events of the 20th century as they impacted on GIT. In the 1917 accounts, for instance, Chairman Harmood Banner mentioned that two thirds of staff were serving in His Majesty’s forces, while Zeppelin raids wreaked devastation within a mile of its offices.

© Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

© John Frost Newspapers / Alamy Stock Photo

© Everett/Shutterstock

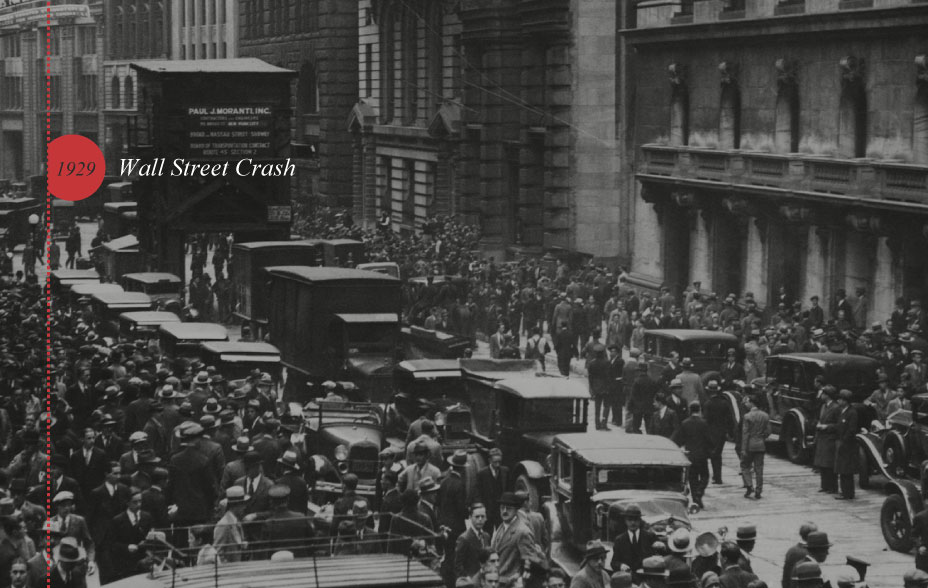

GIT continued to serve its mainly income-seeking shareholders through the Roaring Twenties. By 1928, the Chairman Gerald Moody’s AGM speech was being accompanied by rousing cheers, rapturous applause and cries of “hear, hear!”. The eve of the 1929 Wall Street Crash may have been the GIT board’s finest hour. Its remarkable prescience about the oncoming cataclysm proved a godsend to investors. By then the managers had shifted over half the portfolio into cash and British Government Securities “in view of the impending collapse of the Stock Exchange boom”. This canny restructuring helped to protect capital values, marked down by only single figure percentages even in the worst years of the 1930s slump, until the tide eventually turned prior to the Second World War.

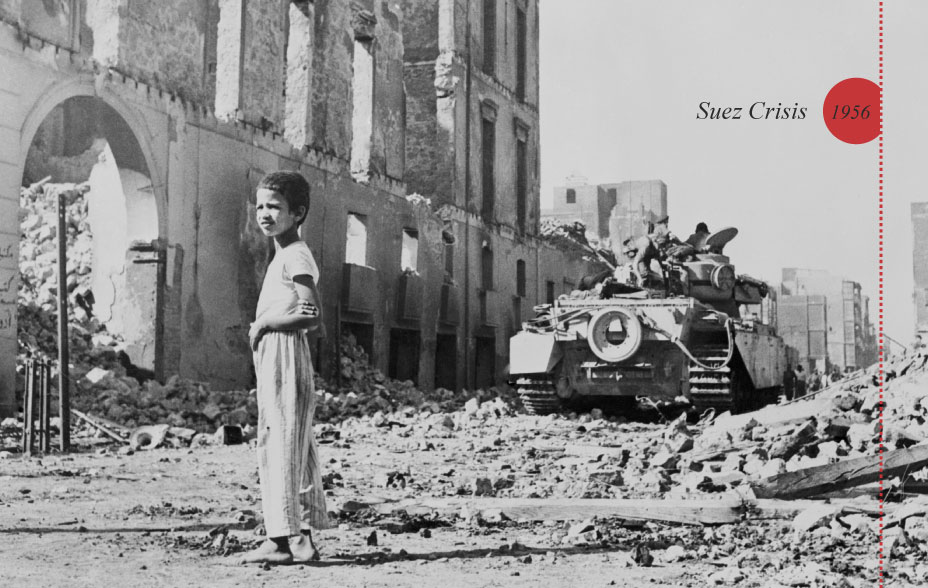

In another timely move, instructions were given at the outbreak of hostilities for “the duplication of our records to places of safety”. This limited damage when the Blitz came, in the words of the annual report “damage to the company’s premises through enemy action have added to our troubles, all of which happily have been surmounted”. In the austerity years of the late 1940s the trust contained a mind-boggling 860 securities, yet, even now, was still less than £3m in size. As the postwar equities boom gathered momentum, GIT evolved from a fixed-income-dominated vehicle into a generalist trust. Total assets reached a still modest £5m by 1957, when “security values [had] declined considerably [as a consequence of] the Suez crisis”. By 1965, assets at last crept past the £10m mark, reaching £20m before the end of the decade.

© Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Other changes were afoot. Since 1948, GIT had shared administration with two other trusts, under the title of the General Investors Group. In August 1971, this group was amalgamated with F&C Management Limited, managers of the Foreign & Colonial Group. Within a year, GIT chairman Roger Wethered was reporting: “this is proving of benefit. Our portfolio is now spread between Great Britain, North America and Australia, to which may be added later a greater stake in Europe when this country enters the Common Market in 1973.” Wethered, incidentally, had achieved fame as an Oxford undergraduate when he narrowly missed a nonchalant win in the 1921 Open Championship in St Andrews, losing in the playoff to a professional.

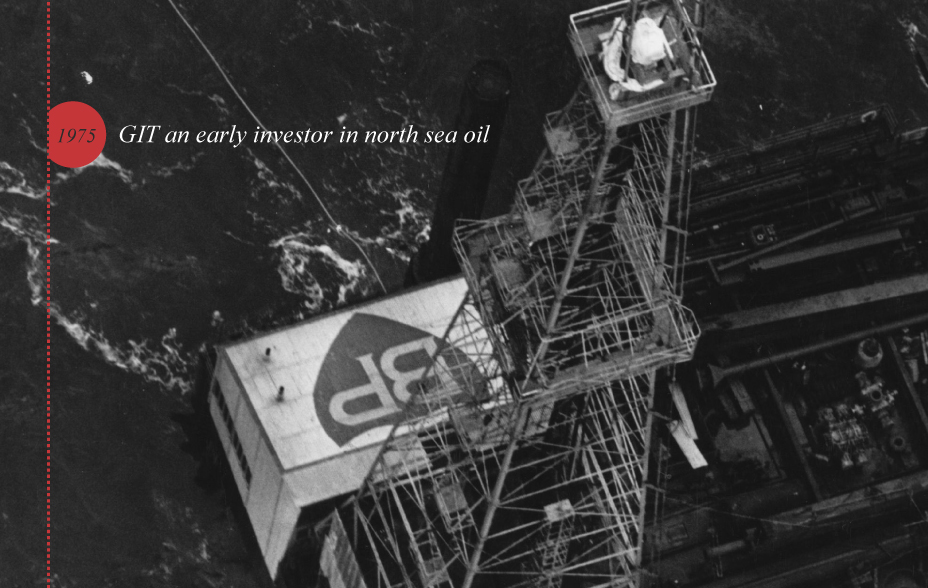

Then came the discovery of North Sea oil, in which GIT was an early investor. It took stakes in Ranger Oil of Canada, BP and what became LASMO, each of which had direct interests in what became the Ninian Field.

© Express/Getty Images

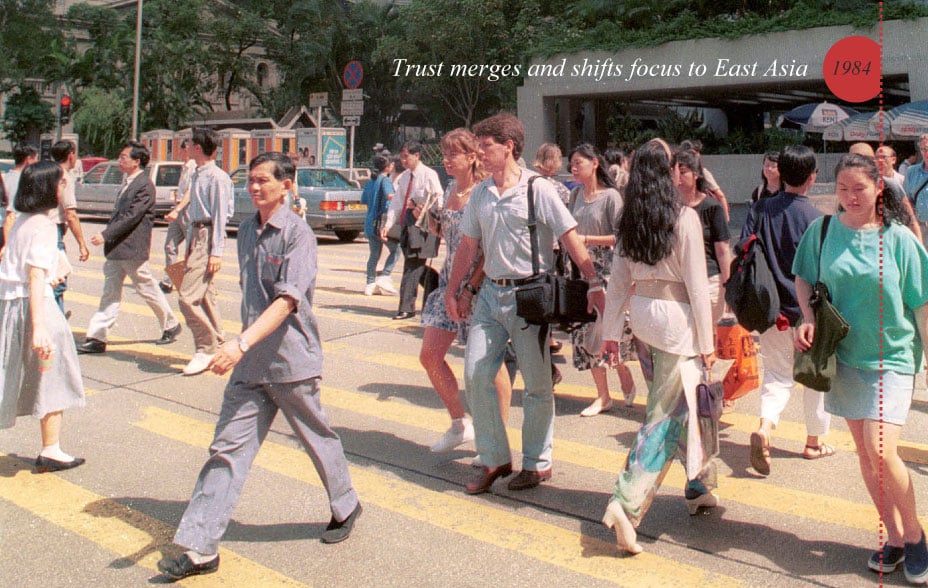

By the early 1980s, the trust had reached two major milestones: £50m in total assets and its 75th birthday. Following the most important strategic review since launch, GIT merged with its stablemate, The Cardinal Investment Trust and refocused on the Pacific Basin: “a growing region embracing some of the most dynamic capitalist economies”. In 1984, the trust was duly renamed F&C Pacific Investment Trust PLC and the next stage of its life began.

By 1987, the now £167m trust had more than doubled in size from the combined net assets of GIT and Cardinal two years previously. A fall of 5 per cent over the next 12 months – a modest setback given that the period spanned “Black Monday” and the great storm of October 1987 – would be followed by a significant rebound. As the 1990s dawned, total assets reached a new high of £234m.

© Michael Porro/Getty Images

As F&C Pacific from 1984 to 2005, and as Witan Pacific from 2005 until 2020, the trust managed to remain at the forefront of Asia Pacific investment for more than 35 years. These years included Japan’s 1990s ‘lost decade’ of zero economic growth, during which, in the chairman’s words, “the Japanese market was reduced to a state of paralysis by the 1995 Kobe earthquake, the rise of the Yen and the aggregation of problems in the financial system”.

Meanwhile global financial markets were hit by two Gulf conflicts, the 1990s equities boom, the internet bubble of 2000-2002, 9/11, the banking crisis of 2008/9 and, most recently, the onset of Covid-19 in early 2020. Investment trusts are nothing if not resilient.

Since its launch by the unconventional Mr Newgass in 1907, the trust has overcome every obstacle, endured every setback, served its shareholders, learned lessons and evolved.

In September 2020, a new era began, with the appointment of Baillie Gifford as managers and company secretaries of the trust, to be managed by Roderick Snell and Sophie Earnshaw. Renamed Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust and, with a new remit focused exclusively on the growing opportunities of China, the next phase begins.

Find out more about Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust

Important Information

The views expressed should not be taken as fact and no reliance should be placed upon these when making investment decisions. They should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. If you are unsure whether an investment is right for you, please contact an authorised intermediary for advice.

This article was produced and approved in May 2021 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of recording and may not reflect current thinking.

The trust’s exposure to a single market and currency may increase risk.

The trust invests in overseas securities. Changes in the rates of exchange may also cause the value of your investment (and any income it may pay) to go down or up.

The trust's risk could be increased by its investment in unlisted investments. These assets may be more difficult to buy or sell, so changes in their prices may be greater.

The trust invests in emerging markets where difficulties in dealing, settlement and custody could arise, resulting in a negative impact on the value of your investment.

The trust can borrow money to make further investments (sometimes known as “gearing” or “leverage”). The risk is that when this money is repaid by the trust, the value of the investments may not be enough to cover the borrowing and interest costs, and the trust will make a loss. If the Trust's investments fall in value, any invested borrowings will increase the amount of this loss.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). The investment trusts managed by Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are listed UK companies. The Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust is listed on the London Stock Exchange and is not authorised or regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

For a Key Information Document for the Baillie Gifford China Growth Trust, please visit our website at www.bailliegifford.com