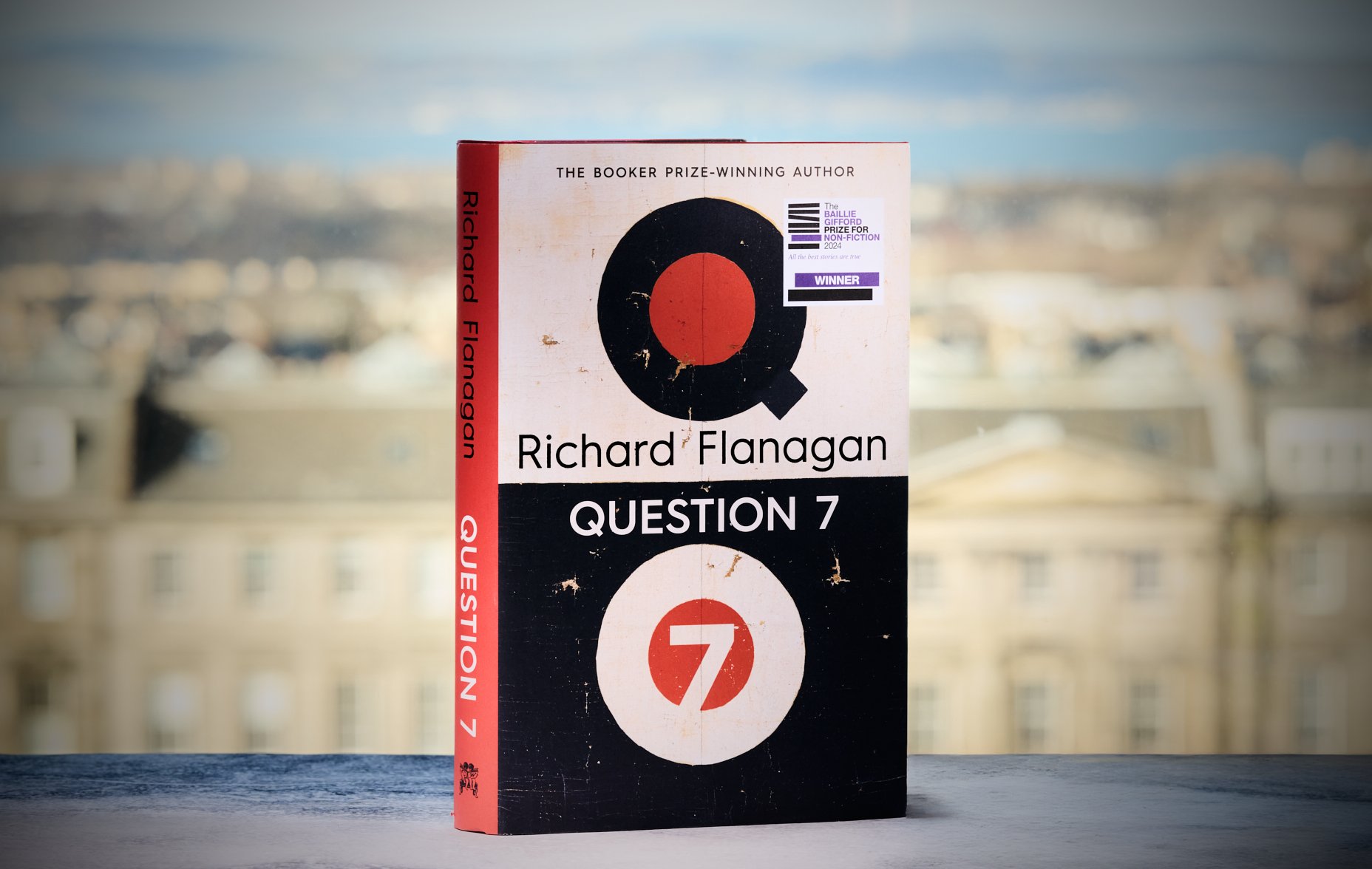

Strangely, the winner of the 2024 Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction was the one we discussed least.

Richard Flanagan’s Question 7 was so blindingly good that, at every stage of whittling down 300 publishers’ submissions, we all knew it would make it through to the final meeting. This luminous and devastating work makes Flanagan the first to win the Booker Prize for fiction and the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction.

The Tasmanian won the Booker in 2014 for his novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North. That unflinching recreation of Australian soldiers’ lives and deaths in a wartime Japanese labour camp haunts his first foray into factual writing.

Intertwined threads

Flanagan bases Question 7’s time-blending structure on an Aboriginal belief that past, present and future are happening simultaneously. It moves from a present-day visit to the site of the camp near Hiroshima where the author’s father slaved for the Emperor, to a story about how a minor sci-fi novel helped change global history.

It climaxes with the author nearly drowning as a young man. It’s a tender exploration of memory, family and what it means to love.

But what sort of a book is it?

An autobiography? Yes, in that it’s the story of Flanagan and his parents’ lives. That closing sequence tells of how he was trapped beneath a waterfall when his kayak became wedged in the rocks.

“When I died on the Franklin River at the age of 21, it was as I had always known it would be. Everything ever since has been an astonishing dream,” he writes. “Increasingly, I expect that in my final moments, I will wake in the river dark, discovering I never left and am now to drown and that the only novel

I ever wrote was my life. Perhaps this is a ghost story and the ghost me.”

Or is it a history book? Yes, in that we learn of the scientific arms race that led Hungarian-born physicist Leo Szilard (1898–1964) to conceive of a nuclear chain reaction after reading HG Wells.

It also covers the fateful consequence. In 1939, Szilard drafted a letter, to be signed by Einstein, warning President Roosevelt of German physics research and possible Nazi destructive capability. That led to the Manhattan Project and the bomb falling on Hiroshima.

Is it, perhaps, a work of fiction? Yes, in that Flanagan imagines scenes from Wells’ famously frisky Edwardian sex life. One erotic encounter, involving the much younger writer Rebecca West, led the sci-fi writer to pen his little-remembered 1914 novel The World Set Free. It foresaw the bomb and tripped Szilard into his terrible eureka moment.

Thus, in a virtuosic braiding of storylines and themes, Flanagan constructs a web of historical interconnectedness, celebrating love and human resilience. Fiction influences fact, sometimes to awful ends.

Baillie Gifford Prize judge Alison Flood

Photography by Duncan Elliott

Echoes of war

Flanagan links his existence all the way back to Wells’ prophetic book via the atom bombs falling on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and his father’s resulting escape from death in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp.

We could argue whether Question 7 is primarily tragedy, romance or excoriating political commentary. It’s all those too. Flanagan grapples with post-colonial questions of what it means to be a white Australian with “convict blood”, with the genocide of the Aboriginal Tasmanians

and the ecocide of the island’s rainforests, relating these to the story of his parents’ love for each other and their family.

I’m not sure it’s possible to know who we are, why we do what we do and love who we love. But in this utterly original memoir/history/fiction/romance/tragedy, Flanagan makes a better attempt than any writer I’ve read to understand themselves.

I emerged bruised and battered by his honesty and clear-sightedness. My heart swelled with tenderness for the world, its beauty and the people in it. As the book’s laconic, recurrent, piercing phrase has it:

“That’s life.”

Question 7 is published by Vintage, Chatto & Windus (hardcover £18.99)

Eye on the prize

What’s the point of book awards? Sir Peter Bazalgette tells Colin Donald why we should celebrate them

“Of the making of books, there is no end,” it says in the Bible. But the process isn’t just endless. Like the universe, it’s expanding.

“There are thousands more titles published annually than there were even 20 or 30 years ago,” notes Sir Peter Bazalgette, the culture and media grandee who chairs The Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction.

“That’s surprising when you think about how new technologies are challenging traditional publishing. Everything from TikTok to YouTube, or whatever social media you care to mention, it’s not just an increasing number of books that’s adding to the noise.”

How many more hardbacks and paperbacks are pouring off the presses? According to media analyst Nielsen, 181,000 titles were published in the UK in 2024. That’s almost a third more than at the turn of the century. Enough to fill a bookshelf about three miles long.

An estimated 80 per cent of those are non-fiction. Baz, as he’s known to everyone who’s met him, thinks the Baillie Gifford Prize is “incredibly important” because it pans for the nuggets amid this abundance.

“The Prize’s job is to highlight real quality, and that’s a vital public service. With each year’s panel of judges – whose backgrounds and political outlooks vary each time – you have five or six very switched-on, intelligent people going through the whole output of the year. They’re carefully curating for you, the reader, what they think are the best books.”

The former TV executive, who hit the commercial motherlode in 2000 with the Channel 4 reality show Big Brother, is a voracious reader who believes awards like this are too much taken for granted.

Sir Peter Bazalgette

A man of passion and persuasion, Bazalgette isn’t short of calls on his time and advocacy. As well as being chairman of the Royal College of Art, the post-graduate school of fine art and industrial design, he is co-chair of the Creative Industries Council, which works with the government to protect and exploit the UK’s hard-won position as an arts, culture and design superpower.

His current focus is on better career paths vital to many areas: augmented reality, broadcasting, gaming, architecture, fashion and retail, to name just some.

As he points out, those industries contribute a chunky 6 per cent of UK gross domestic product and could do more with greater public investment and added awareness from school careers officers and aspirational parents.

Indirectly, Bazalgette believes non-fiction writing and the debates it engenders are a huge contributor to the rich cultural mulch in which the UK’s creativity germinates.

“The people who write these books spend years researching and writing them. Works of that quality need to be listened to. In non-fiction, they’re often ‘important’, whether culturally, like the biography of John Donne, Super-Infinite, in 2022, or politically and environmentally, like the 2023 winner Fire Weather, or 2024’s partly polemical Question 7.

Bazalgette credits chief executive Toby Mundy with the Prize’s organisational heavy lifting. But as umpire and figurehead, he has become increasingly outspoken about its role in “championing a free exchange of ideas, however provocative or uncomfortable they may be”.

By this, he’s referring to controversies, including those surrounding Baillie Gifford’s now terminated relationship with UK book festivals. These have forced arts organisations to think carefully about sponsorship’s role in sustaining cultural conversations, the ethics of social media campaigning and how to respond to it.

“The longlisted books are full of big ideas, and the promotion of those depends on having a backer who supports that free discussion. Sponsors should be applauded for stepping up, not criticised, particularly when the grounds for criticism are so spurious.”

There’s no doubt that book prizes are commercially important to publishers – Baillie Gifford Prize winners typically see a 10-fold increase in sales the week after the award. But Bazalgette’s point is that their greater significance rests in how they help make sense of an increasingly cacophonous world. And in that task, any help is welcome.

Important information

The views expressed in this article should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. The article contains information and opinion on investments that does not constitute independent investment research, and is therefore not subject to the protections afforded to independent research.

Some of the views expressed are not necessarily those of Baillie Gifford. Investment markets and conditions can change rapidly, therefore the views expressed should not be taken as statements of fact nor should reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Both companies are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and are based at: Calton Square, 1 Greenside Row, Edinburgh EH1 3AN.

142707 10053719