All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk.

The tailwinds behind China’s economic growth have turned. Between 2015 and 2021, the US dollar value of Japanese exports to China grew by 50 per cent. Since then they have fallen over 20 per cent. For some of our holdings, the severity of the downturn has been exacerbated by exposure to more affected areas, such as fixed asset investment or the wealthier, property-owning consumer.

My trip to Shanghai and Shenzhen, my first in just over four years, was a chance to meet the Chinese competitors of some of our Japanese holdings, as well as to meet a few Japanese companies and speak with the executives of their subsidiaries. It was an opportunity to disentangle cyclical from structural challenges, balance the opportunity from alignment to China’s economic and technological progression against the potential threat of substitution, and measure the depth of competitive moats.

What happens in China is still very important to many of our Japanese holdings. The country represents about a third of sales for Shiseido, FANUC, SMC and ROHM and half of sales for Murata.

One striking feature of my visit was the frequency with which I was asked about comparisons of today’s China with Japan at the start of the 1990s. Japanese per capita GDP rose from $10,000 in 1980 to $26,000 in 1990, but in 2022 it was only a little higher, at $34,000. Prices and wages scarcely changed for much of the period from 1990 until very recently. Chinese per capita GDP was $13,000 in 2022, roughly where Japan’s was in the mid-1980s just before the bursting of the asset price bubble.

Between 1986 and 1990, Japanese house prices rose more than 150 per cent. In Shanghai, they did similarly between 2014 and 2020. It took almost 30 years for Tokyo condominium prices to recover to the level of 1990.

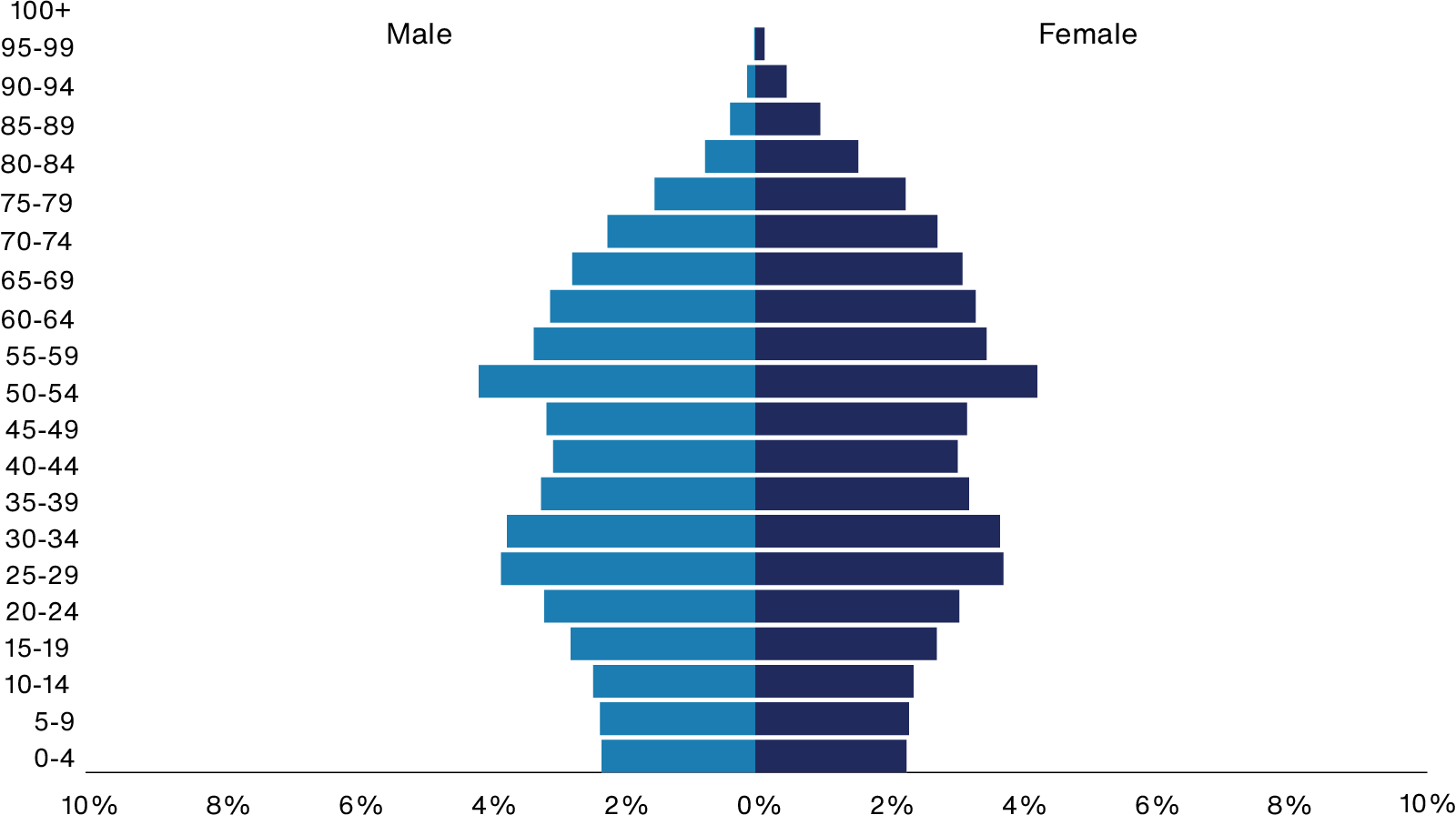

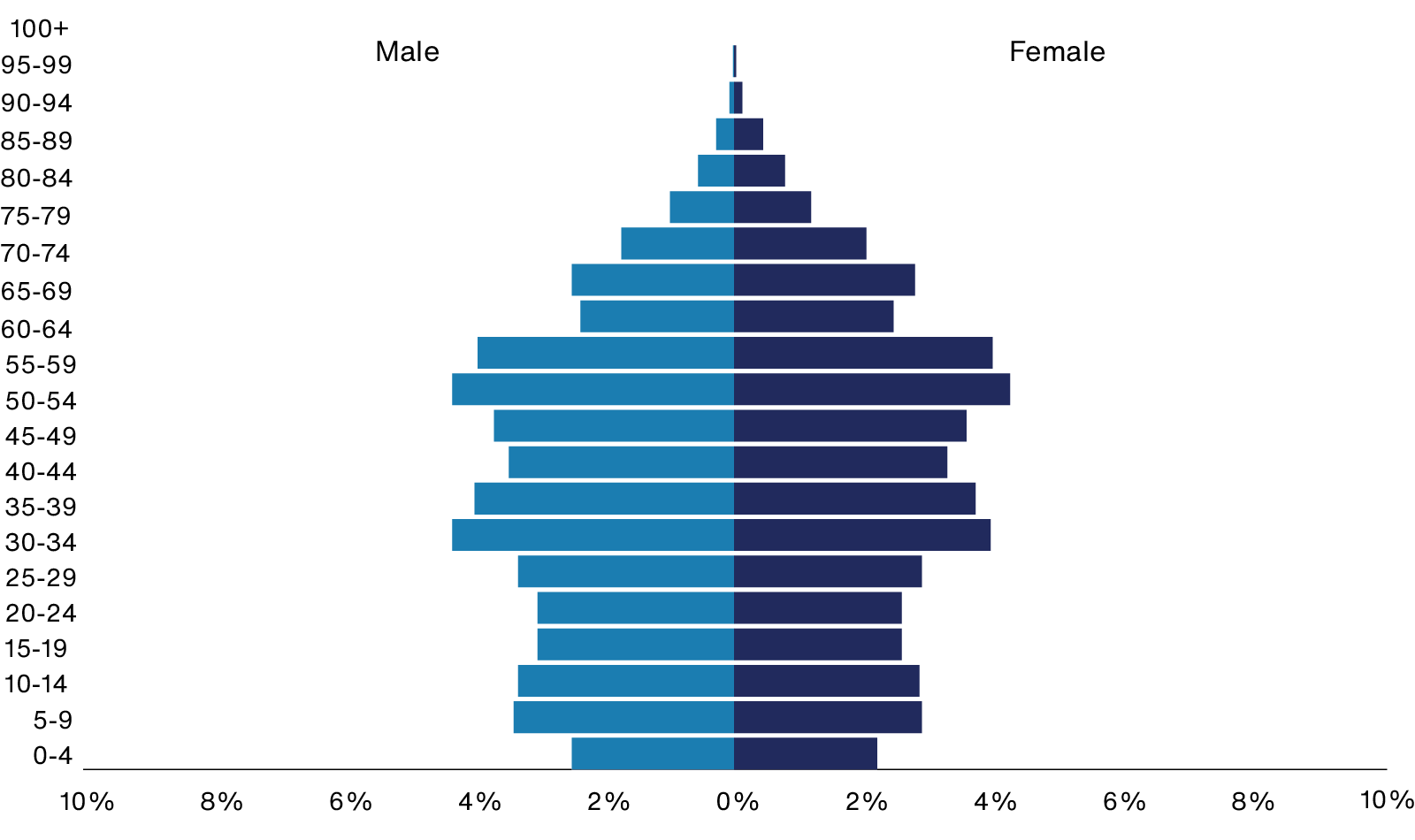

Just as importantly, China’s demographic pyramid in 2022 looks remarkably similar to Japan’s in 2002. Many fear that China may mimic Japan economically but, in doing so, ‘become old before it becomes rich’.

Japan 2002

Population: 127,301,750

China 2022

Population: 1,425,887,336

Source: PopulationPyramid, 2023.

Accepting that, viewed top-down, growth is unlikely to be as strong in the next 10 years as in the past, it is hard, looking bottom-up, not to be at least partially optimistic about the opportunity for Japanese companies.

Technological strides

If China’s economic growth has slowed, its technological momentum has not. The country’s robot density, a measure of the number of industrial robots per employee, is still 20 per cent below Japan’s (and a third of South Korea’s). The Chinese middle class is over twice the size of the entire population of Japan, but even attributing all of the spending on cosmetics to the most affluent 25 per cent of the population, it still comes out spending 20 per cent less per capita than the Japanese . More tangentially, there are just 175 dentists per million in China compared to 608 in the US and 810 in Europe. This is a small part of the investment case for recently purchased Nakanishi, which makes dental tools, and which recently acquired a Chinese dental equipment manufacturer to strengthen its presence there.

Another interesting observation for me was how well the Chinese companies I met had navigated Covid-19’s disruption. Mindray, China’s leading medical monitors and diagnostics company, has doubled sales since 2019. Inovance, an industrial automation and power systems maker based in Shenzhen, has grown sales fourfold. It attributed this to the resilience and integrated nature of its supply chain and local talent pools. Meanwhile, international players have struggled, with sourcing semiconductors, for example. As a result, Inovance has received accreditation more quickly and will probably become a more prominent competitor to the likes of Yaskawa or Nidec.

Mindray acknowledges that this progress is easier in developing markets than in the more heavily regulated markets of North America and Europe and, while this may protect our Japanese holdings to some extent, it will still narrow some of their growth opportunity.

Competing on quality

It is also striking, when comparing these Chinese industry champions to Japanese peers, that both operate in fiercely competitive local markets and have learned to hone their edge through quality and technology rather than solely on price. Gross profit margins are comparable but operating margins are invariably higher in China. This is a measure of different marketing and service approaches and of course labour costs, which may be unsustainable if they follow through on their global expansion ambitions. Olympus’ gross and operating margins last year were 68 per cent and 21 per cent, compared to Mindray’s 65 per cent and 35 per cent.

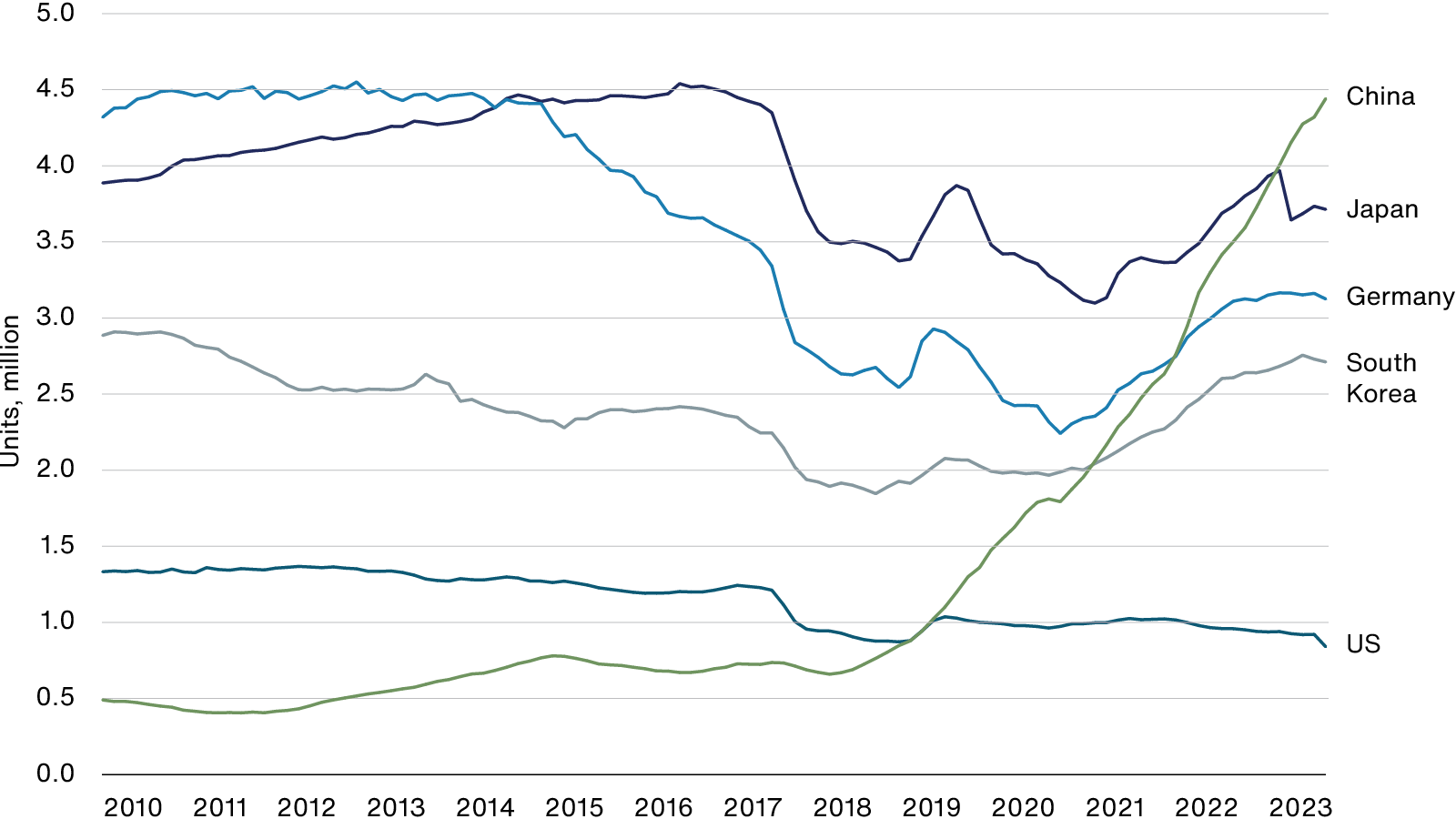

China’s advancement in automotive drivetrain electrification is fairly well recognised. A quarter of new car sales in China last year were fully electric and the country has an enormous cost, and now scale, advantage in battery materials and technology integration. China’s NIO claims a 1,000km-plus range on its ET7, further than the solid-state battery cars Toyota Motor is developing for production in 2028.

Perhaps less well understood are the achievements and capabilities of Chinese ‘level 3’ autonomous driving and that vehicles showcasing this technology can be bought for just $28,000. It is no wonder that China has now surpassed Japan as the largest exporter of cars – it gives us another reason for caution on Japanese manufacturers in the longer term.

Exports of passenger cars

Source: Bloomberg. Data as at 31 March 2024. Rolling 12-month sum.

My meetings with FANUC, its competitors and industrial automation distributors reinforced my view of the sustained edge of Japan’s robotics. Inovance regards FANUC’s robots and Yaskawa’s servo motors – high-precision motors used to control machine movement – as the standard to which they aspire, implying a persistent gap.

Japan still leads when it comes to heavier payloads, a reason for its dominance in the automotive industry, and multi-axis arms. Japanese robotics firms still benefit from the entrenched, habit-forming nature of factory automation. FANUC is best known for making standard robots and yet the Chinese CEOs’ focus was on capitalising on a better understanding of customer value, integrating OT (operation technology) with IT and maximising lifetime value for the customer.

One manifestation of this was the extent to which FANUC’s Shenzhen showroom was dedicated to its collaborative robots, coloured green to indicate safe interaction with humans, and the range and complexity of tasks they could perform. FANUC now claims to be the world’s second-largest industrial, collaborative robot maker behind Universal but, by virtue of its position in China, it is far faster-growing.

From cosmetics to chips

Our investments in Japanese cosmetics companies have faced numerous headwinds since taking initial holdings during Covid, most notably a slow recovery in Chinese travel, competition in inbound ecommerce (CBEC) and the negative media surrounding the release of IAEA-approved nuclear wastewater. Japanese-sounding brands have fared far worse than the Clé de Peau Beauté, Decorté and NARS lines from the same makers.

Meetings with Shiseido and KOSE management confirmed that these issues are now dissipating: social media pays less attention to Fukushima, brand equity is unimpaired (independently, Japanese brands are still recognised for “Asian quality, technology and indulgence”) and marketing is resuming. Both Shiseido and KOSE are far more conscious of the daigou (cross-border exporting) arbitrage and how to overcome this – ironically, their promotion of the enduring nature of their brands contributed to the ease of arbitrage.

The years between 2015 and 2020 have been described as the ‘gorgeous six years’ for Chinese cosmetics when rapid market growth was assured, but brand investment lagged. The subsequent years have been tougher, but a valuable wake-up call. Ultimately, the Japanese cosmetics companies (including KAO, which owns Kanebo) look as though they will emerge smarter, delving more into underexploited customer data, building the social commerce presence and generally being faster to market. Shiseido’s Drunk Elephant is one of the top-performing brands on the cosmetics platform Sephora in the US but is only now being brought to China. Brand development is, however, becoming more localised and responsive. Shiseido’s management also argues that Chinese brands’ spending on marketing rather than research and development (R&D), while helping to raise social media awareness for the likes of Proya, is a less sustainable strategy over the long run.

The semiconductor landscape is even more complex. China is the world’s top semiconductor consumer, accounting for more than a third of global demand. Yet it produces perhaps a tenth of what it consumes, lagging behind Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and the US. Over the next five years, this will change. Given the supply-demand mismatch and geopolitical tensions, China has been localising production but has struggled to develop and, increasingly, to obtain from outside the most sophisticated chip-making technology. While technically possible to manufacture sub-14 microns (a micron is a thousandth of a millimetre) using older lithography equipment, this raises costs and reduces yields, meaning that Chinese chipmakers’ costs are sometimes 40-50 per cent more than competitors such as TSMC.

According to a meeting with a senior executive with STMicroelectronics, a Swiss semiconductor maker, state-supported Chinese companies are building a coordinated ecosystem of fabless chip design, where companies outsource the manufacturing of chips to third-party foundries, but they’re also rapidly localising semiconductor equipment. In 2021 alone, the use of local-made equipment increased by 14 points to 35 per cent. Yet China’s semiconductor manufacturing competitiveness still lags behind global leaders, particularly in logic. The localisation rate for CPUs (central processing units), Dynamic RAM, and NAND flash memory is still in single digits. On the other hand, ADAS (advanced driver assistance systems) doesn’t require leading-edge chips, a reason both for the investment into lower-performance power semiconductors and silicon carbide (SiC) and the rapid advancement China is proving without foreign technology.

We need to be aware of this, given our holding in ROHM. From my meetings with the company, there is still strong validation of the strength of its SiC and power device technology. Other analogue areas will be the next to face Chinese competition, though there is still a considerable cost and quality gap in areas such as the passive components made by Murata or advanced packaging, where processes are not always geared to mass production.

Adaptability matters

A consistent theme throughout my meetings with Japanese companies and their Chinese competitors was the pace of learning in China. As a fast adopter, more flexible in its approach to R&D than Japan. Whereas Chinese companies used to take dictation from their longer-industrialised mentors, they’re now beginning to teach Japanese competitors – our portfolio companies included – some valuable lessons. What they learn helps them maintain an edge. This is a big shift in the Japanese mindset.

In 2021, Shanghai school authorities removed compulsory English from final exams to “ease the academic burden” and some of the top Chinese universities are scrapping an English test on entry. China has a linguistic barrier similar to Japan, and this is possibly becoming more entrenched as it asserts itself globally. Given the size of the domestic opportunity, many Chinese companies have been able to scale and hone their technology, especially as the global economy stalled during Covid and particularly where there is strong alignment with state aims.

On the other hand, this is a model optimised for the home market. It comes with social obligations and, as we have learned from many of our Japanese investments, local success doesn’t assure the same overseas, even after mergers and acquisitions of overseas firms have been made.

While the challenge from China to Japanese corporate success is clearly growing, so too is management’s ability to adjust. It is doing this by becoming less compliance-led and cautious than head office might normally dictate. That means being more responsive to local conditions and more inclined to take risks.

Risk Factors

The views expressed should not be considered as advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold a particular investment. They reflect opinion and should not be taken as statements of fact nor should any reliance be placed on them when making investment decisions.

This communication was produced and approved in May 2024 and has not been updated subsequently. It represents views held at the time of writing and may not reflect current thinking.

Potential for Profit and Loss

All investment strategies have the potential for profit and loss, your or your clients’ capital may be at risk. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

This communication contains information on investments which does not constitute independent research. Accordingly, it is not subject to the protections afforded to independent research, but is classified as advertising under Art 68 of the Financial Services Act (‘FinSA’) and Baillie Gifford and its staff may have dealt in the investments concerned.

All information is sourced from Baillie Gifford & Co and is current unless otherwise stated.

The images used in this communication are for illustrative purposes only.

Important Information

Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford & Co Limited are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Baillie Gifford & Co Limited is an Authorised Corporate Director of OEICs.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides investment management and advisory services to non-UK Professional/Institutional clients only. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford & Co and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited are authorised and regulated by the FCA in the UK.

Persons resident or domiciled outside the UK should consult with their professional advisers as to whether they require any governmental or other consents in order to enable them to invest, and with their tax advisers for advice relevant to their own particular circumstances.

Financial Intermediaries

This communication is suitable for use of financial intermediaries. Financial intermediaries are solely responsible for any further distribution and Baillie Gifford takes no responsibility for the reliance on this document by any other person who did not receive this document directly from Baillie Gifford.

Europe

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited provides investment management and advisory services to European (excluding UK) clients. It was incorporated in Ireland in May 2018. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is authorised by the Central Bank of Ireland as an AIFM under the AIFM Regulations and as a UCITS management company under the UCITS Regulation. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is also authorised in accordance with Regulation 7 of the AIFM Regulations, to provide management of portfolios of investments, including Individual Portfolio Management (‘IPM’) and Non-Core Services. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited has been appointed as UCITS management company to the following UCITS umbrella company; Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc. Through passporting it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Frankfurt Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in Germany. Similarly, it has established Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (Amsterdam Branch) to market its investment management and advisory services and distribute Baillie Gifford Worldwide Funds plc in The Netherlands. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited also has a representative office in Zurich, Switzerland pursuant to Art. 58 of the Federal Act on Financial Institutions (“FinIA”). The representative office is authorised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA). The representative office does not constitute a branch and therefore does not have authority to commit Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited, which is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford & Co. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and Baillie Gifford & Co are authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

China

Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Shanghai) Limited

柏基投资管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGIMS’) is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and may provide investment research to the Baillie Gifford Group pursuant to applicable laws. BGIMS is incorporated in Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’) as a wholly foreign-owned limited liability company with a unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL6KQ30. BGIMS is a registered Private Fund Manager with the Asset Management Association of China (‘AMAC’) and manages private security investment fund in the PRC, with a registration code of P1071226.

Baillie Gifford Overseas Investment Fund Management (Shanghai) Limited

柏基海外投资基金管理(上海)有限公司(‘BGQS’) is a wholly owned subsidiary of BGIMS incorporated in Shanghai as a limited liability company with its unified social credit code of 91310000MA1FL7JFXQ. BGQS is a registered Private Fund Manager with AMAC with a registration code of P1071708. BGQS has been approved by Shanghai Municipal Financial Regulatory Bureau for the Qualified Domestic Limited Partners (QDLP) Pilot Program, under which it may raise funds from PRC investors for making overseas investments.

Hong Kong

Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited

柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited and holds a Type 1 and a Type 2 license from the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong to market and distribute Baillie Gifford’s range of collective investment schemes to professional investors in Hong Kong. Baillie Gifford Asia (Hong Kong) Limited

柏基亞洲(香港)有限公司 can be contacted at Suites 2713-2715, Two International Finance Centre, 8 Finance Street, Central, Hong Kong. Telephone +852 3756 5700.

South Korea

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is licensed with the Financial Services Commission in South Korea as a cross border Discretionary Investment Manager and Non-discretionary Investment Adviser.

Japan

Mitsubishi UFJ Baillie Gifford Asset Management Limited (‘MUBGAM’) is a joint venture company between Mitsubishi UFJ Trust & Banking Corporation and Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited. MUBGAM is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Australia

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited (ARBN 118 567 178) is registered as a foreign company under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and holds Foreign Australian Financial Services Licence No 528911. This material is provided to you on the basis that you are a “wholesale client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). Please advise Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited immediately if you are not a wholesale client. In no circumstances may this material be made available to a “retail client” within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act.

This material contains general information only. It does not take into account any person’s objectives, financial situation or needs.

South Africa

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered as a Foreign Financial Services Provider with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority in South Africa.

North America

Baillie Gifford International LLC is wholly owned by Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited; it was formed in Delaware in 2005 and is registered with the SEC. It is the legal entity through which Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited provides client service and marketing functions in North America. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is registered with the SEC in the United States of America.

The Manager is not resident in Canada, its head office and principal place of business is in Edinburgh, Scotland. Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is regulated in Canada as a portfolio manager and exempt market dealer with the Ontario Securities Commission ('OSC'). Its portfolio manager licence is currently passported into Alberta, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Newfoundland & Labrador whereas the exempt market dealer licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford International LLC is regulated by the OSC as an exempt market and its licence is passported across all Canadian provinces and territories. Baillie Gifford Investment Management (Europe) Limited (‘BGE’) relies on the International Investment Fund Manager Exemption in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Israel

Baillie Gifford Overseas Limited is not licensed under Israel’s Regulation of Investment Advising, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law, 5755-1995 (the Advice Law) and does not carry insurance pursuant to the Advice Law. This material is only intended for those categories of Israeli residents who are qualified clients listed on the First Addendum to the Advice Law.